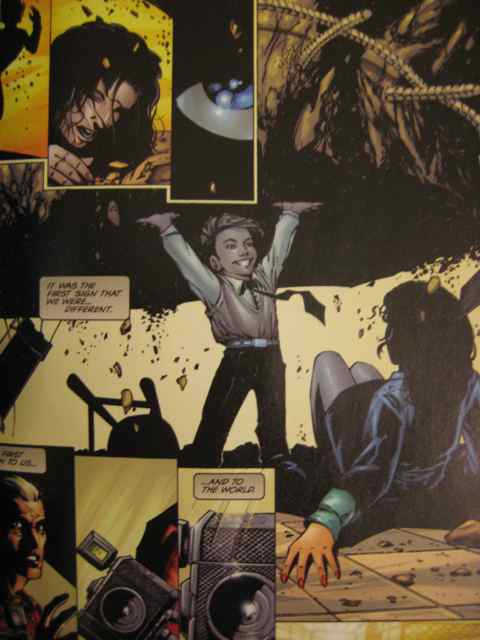

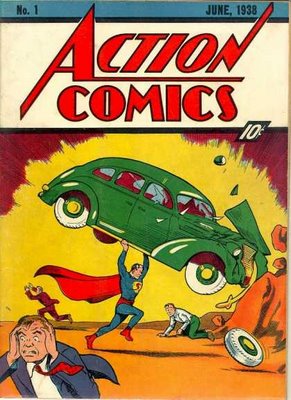

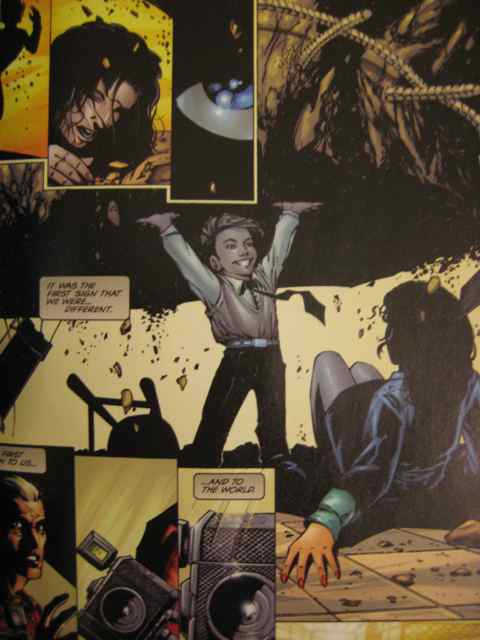

The boy's name is Matthew Bright. It is the first indication that anyone in the town of Pederson, Illinois, is different, or rather special, and it is one of the key images of Joe Straczynski's comic book masterpiece Rising Stars. The image seems to have its roots in the cover of Action Comics #1 (the first appearance of a slightly better known hero by the name of Superman) and it recurs three more times in the story, even once with a car. It defines Bright, one of the story's key characters, and his determination to put the lives of others before his own.

Straczynski is perhaps best known for Babylon 5. That was a TV show that was revolutionary, groundbreaking and other similar plaudits. He set out, in the world of US television, where shows are cancelled on whims, to tell a five year story. For the most part, he succeeded. This is the more impressive given that at the time no US Sci-Fi series that wasn't Star Trek had lasted more than a season. Of course, these days, long running Sci-Fi shows are ten a penny. Babylon 5 led the way.

Rising Stars is not nearly as unprecedented, or indeed at all unprecedented. But it is no less great for it. Its premise owes a lot to Watchmen (covered several years ago in Part I of this series), in that it is the story of how the world would be different had the one hundred and thirteen people who were in the womb at the time of a blinding flash over the skies of Pederson been imbued with super powers as a result (in an effort to confuse non-American readers, Straczynski refers to them being in utero rather than the womb - at least, I'm assuming the term is familiar in the US).

Of course, the key difference between Rising Stars and Watchmen is that the former is overall a brighter and more uplifting tale. That's not to say it's without a darker side; it isn't. Early on the children are taken into the care of a government that never loses its terror of them; child abuse, loneliness and bullying; the divisions and flaws of the specials themselves are magnified by their abilities; one particularly religious parent uses their child for financial gain.

There is a general theme of exploitation which runs through the series, both by outside forces and in the way some specials exploit others, testifying against them in an eerily McCarthyite way when things fall apart and degenerate into civil war. Other specials are exploited by corporations or criminals, both for their gifts and their brands.

Indeed, there is a strong strand of rhetoric that seems inspired by McCarthy, both in the way those in power are in such fear and also in the way they act on that fear: we don't know who these people are or what they might do so they must be stopped just in case. These are some of the most powerful and chilling aspects of Straczynski's story.

Yet in spite of all the darkness, it is still a broadly uplifting story. Not simply in terms of Matthew Bright, but also elsewhere. In a beautiful scene, Willie Smith, who is fat, only able to hover a few feet off the ground and bullied for it, suddenly snaps and soars away, higher and higher, until he vanishes from sight, not to return.

In a second key similarity to Watchmen, the early plot is driven by a series of murders of the specials and we follow the story's anti-hero John Simon, or Poet, as he investigates the deaths and as events spiral gradually out of control. The narrative is divided into twenty-four issues that span three distinct acts. It is worth noting that this would make an excellent film trilogy and in these days when comic book adaptations seem almost too plentiful it is surprising we haven't had one.

And Straczynski employs other narrative techniques from that seminal comic. He nicely bridges the decade between the first two acts with a press article, which not only catches us up, but nicely shows how differently the world outside views events based on their incomplete picture. It also does far more than just provide background, moving the story forward in crucial ways.

There are too many nice touches to mention all of them, from specials who go their whole life without realising they're special, to Straczynski's brilliant orchestration of the descent of events into chaos, something he managed with similar elan in Babylon 5. And while most of the superpowers are fairly run of the mill, a little Superman here or Human Torch there, some are rather creative, in particular one indestructible person whose power turns out not to be quite so awesome in reality as it might appear on paper. Dr Welles, the physician appointed to look after the specials as children, but in one of the comic's creepy turns also to analyse their weaknesses, is a particularly interesting creation and the relationships he forms with the specials is one of the story's most touching aspects.

All that said, it is not perfect. Straczynski's writing can get a touch indulgent in places. Then there is his penchant for recycling things. Joshua wonders at one point if God can forgive the sins we keep secret. Given God is supposed to be omniscient (and, coming from the highly religious background he does, Joshua surely knows this) it seems a little odd. Stracznyski appears to be trying to rerun the much better question he asked much more powerfully in Babylon 5 of how we can ask for forgiveness of the sins we do not know we have committed. Then there is a vice-president feigning illness to avoid an assassination. While this doesn't seem to carry quite the weight it did in B5, on the plus side it doesn't have the gaping plot holes that it did then. Another idea first floated in B5 is the potential of telekinesis which can only manipulate very small items. In fairness, he didn't really run with it then, but he also doesn't make the most of it here.

Particularly towards the end, it feels a little conspiracy theory happy. This is probably great if you like that sort of thing, but even then it's laid on a little thick. Yet despite having unearthed all the dirt in Washington, which we are told will give special Randy Fisk everything he needs to get into the White House, he then doesn't use it and goes on to lose two elections (which seems odd given you would think a real life super hero would poll well given the regard the public has for politicians in general), finally gaining office only through a freak coincidence.

At times things feel too simplistic - I'm not sure the Israel/Palestine conflict would be much more tractable if there was more water there. Simply building factories doesn't create jobs. This last shares a little similarity with one of the issues of Straczynski's justly ill-fated run on Superman. Ordinary citizens putting on superhero masks so they can witness crimes but also pat neighbourhood children on the head just looks downright creepy. That said, some things, such as the executive order forcing companies to put their outlet pipes upstream of their intake pipes in order to tackle pollution of rivers is a very neat idea. Also, though issue 17 is titled Change the World and this is the dominant theme for the third act, it is very US centric and while one or two changes, such as that in the middle-east and the issue of nuclear disarmament, are global, for the most part it is the US that gets changed and that the specials help.

In general, Straczynski's plotting is meticulous, with seeds planted early on blooming in wonderful and surprising ways down the road. Unfortunately, the other side of this is that the odd slip in this regard sticks out like a sort thumb, such as super intelligent genius Brody Kempler's somewhat out of left-field introduction in issue 17. Given how crucial he is, it feels odd he's had not a mention before. But this is the exception. In contrast, many characters have powerful arcs from hero to villain and then back to redemption. There's a nice poignancy as, late in the story, one such special dies in a futile last stand against an army that's been sent to kill him just to prove they can, uttering the line "after all, I'm a... a hero.", which, given what's come before, has a heavy emotional weight. Say what you like about Straczynski, he can write a good death and there a number of similarly moving ones here, either with a hero trying to help to the last, some that are powerful simply for their senselessness, or others who die blamelessly and unintentionally.

The final few issues do, in many ways, feel weaker than what has come before. Part of these problems may be down to the delays that occurred when publication ground to a halt amid a dispute between Straczynski and publishers Top Cow. This delayed the final three issues by two years. Despite that the overall ending works nicely and satisfyingly brings things full circle, though for Matt and many of the other specials it does feel a little rushed and oddly, given the nature, slightly anti-climactic.

I haven't really mentioned art. In large part that's down to my own personal preferences in placing higher importance on words than pictures in comics. That said, though drawn by various different artists over the run, the art is generally very good and the style remains consistent enough. It aids the story well, though for me it never steals the show.

It may seem like I've listed a lot of flaws for something I'm describing as a great work, but despite all of them it is a compelling story well told. Ultimately, it is one of my favourite comics of all time and one I return to far more often than Watchmen. But then there is a very important distinction between favourite and absolute greatness, though Rising Stars, for all its faults, is still great. Great for the more positive and inspiring messages and themes that shine through it, great for the darker contrasts which make that possible, and great for the image of the boy holding up the sky.

No comments:

Post a Comment