We've reached that time of year again...

Best Opera: Not as good a year as 2011. Honorable mentions go to Aldeburgh Music's marvellous Knussen double bill, the Opera North Norma and the Berlin Phil/Rattle/Kozena concert performance of Carmen but the palm goes to ENO's superb new production of John Adams's modern masterpiece The Death of Klinghoffer reviewed here. A work which, as I said at the time, deserves to be staged widely and to remain firmly in the repertoire.

Worst Opera: There was a lot of very indifferent opera in 2012 but most of it was badly flawed in one category rather than across the board. Thus ENO's Julius Caesar and the Bayreuth Tristan were both awful productions but had redeeming musical qualities. So the award goes to an opera which I didn't review at the time, the awful Judith Weir Miss Fortune at the Royal Opera back in the spring.

Best Play: It's been a real bonanza year for theatre, even if much of it has been inexplicably over-looked by other awarding bodies. Josie Rourke's opening season at the Donmar was of generally high quality. The National had a number of gems of which the beautifully acted, moving Moon on a Rainbow Shawl deserved way more plaudits than it received. Gatz and the Yugoslavian-Albanian Henry VI were in different ways fascinating. However there were three plays which stood head and shoulders above the rest in all departments: the West End revival of Long Day's Journey into Night, the Chichester Arturo Ui and the Hampstead 55 Days.

Worst Play: The biggest disappointment of 2012 was the Almeida King Lear of which I had high hopes this time last year, but it was just dull and unenvolving rather than awful (the Almeida in general I'm afraid had an indifferent year). Big and Small avoids the palm by virtue of the presence of Cate Blanchett. Several works at the Edinburgh International Festival unsurprisingly came close, but are just saved by the Chichester Heartbreak House which was regrettably poor in every department.

Saturday 29 December 2012

Sunday 23 December 2012

Where's Runnicles' favourite recordings issued in 2012

2012 has been a good year for recordings, of which more in a moment. However before I get onto that, I find I must rectify two omissions from last year's list. The first is Mark Elder and the Hallé's majestic account of Vaughan Williams' London Symphony. I'm not sure how this escaped my notice on release since I'm a fan of the Hallé's label. The disc is for me the more impressive as I'm not the world's greatest Vaughan Williams fan, yet my first impulse on listening to it was to put it on again immediately.

The second omission is this BIS disc of Anders Hilborg works. This is actually a fortuitous omission since it ties in nicely to one of the themes of my music buying this year, which has shifted heavily towards digital downloads, which the independent labels do far better. I came across this via the eClassical store (which I've written about extensively here), and after staring at the intriguing cover image for a while, decided to give it a go. The four works on the disc are all performed by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, but with different conductors (Esa Pekka Salonen, Alan Gilbert and Sakari Oramo). King Tide, for which Oramo is on duty, is probably my favourite, fascinating because it feels both organic in the way the climaxes grow but also industrial at the same time. Hillborg creates generally energetic and intriguing sound worlds. He writes well for all sections of the orchestra and often yields a sound somewhat akin to a synthesiser, perhaps unsurprising given the liner notes mention a background in electronic music. (I mean that as a compliment, incidentally.) At times frantic, tranquil or muscular, and moving effortlessly between, it is an impressive disc and Hillborg is definitely a composer to watch.

The second omission is this BIS disc of Anders Hilborg works. This is actually a fortuitous omission since it ties in nicely to one of the themes of my music buying this year, which has shifted heavily towards digital downloads, which the independent labels do far better. I came across this via the eClassical store (which I've written about extensively here), and after staring at the intriguing cover image for a while, decided to give it a go. The four works on the disc are all performed by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, but with different conductors (Esa Pekka Salonen, Alan Gilbert and Sakari Oramo). King Tide, for which Oramo is on duty, is probably my favourite, fascinating because it feels both organic in the way the climaxes grow but also industrial at the same time. Hillborg creates generally energetic and intriguing sound worlds. He writes well for all sections of the orchestra and often yields a sound somewhat akin to a synthesiser, perhaps unsurprising given the liner notes mention a background in electronic music. (I mean that as a compliment, incidentally.) At times frantic, tranquil or muscular, and moving effortlessly between, it is an impressive disc and Hillborg is definitely a composer to watch.

Tuesday 18 December 2012

The Effect at the National, or, Yours Truly Wonders What Fellow Critics Are On

This show, I discovered on re-reviewing the reviews this morning, was even more overwhelmingly praised than I had thought. I cannot for the life of me think why. Of course, from my point of view it started with two big handicaps. The director was Rupert Goold, who has as yet failed to impress me, and the female lead was Billie Piper, who with my Doctor Who fan hat on made me grit my teeth in annoyance almost more than one or two particularly infamous companions of the classic series I could mention. Nevertheless, I retain, I hope, the capacity to have my prejudices overcome. Goold, Piper and their fellow collaborators largely failed to achieve this.

I didn't see Lucy Prebble's ENRON so I can't compare the two works, but this play for me committed a cardinal sin. It is a play about issues. Rather too many issues frankly including the nature of love, the morality of the drugs companies, the problems involved in tackling depression, or helping someone who is suffering from depression. These issues require a great deal of talk. Now I like a play with a message (see 55 Days or the best of Shaw when he's well done), but Prebble makes the mistake of sacrificing character for issues. The result was one which I have remarked on before and which is usually fatal for me in terms of my view of a piece, apart from one or two fleeting moments I didn't give a damn about any of the people on stage. I would also note that very similar subject matter has been far more effectively treated in the musical Next to Normal which sadly never made it to London.

The performers are nothing to write home about either. They're all perfectly solid, but nothing really leapt out and took me by the throat, though it is only fair to say they aren't helped by the material. Piper and Anastasia Hille as the depressed doctor have moments which do suggest that with a better script they could really shine, but it's not enough to save the evening.

I didn't see Lucy Prebble's ENRON so I can't compare the two works, but this play for me committed a cardinal sin. It is a play about issues. Rather too many issues frankly including the nature of love, the morality of the drugs companies, the problems involved in tackling depression, or helping someone who is suffering from depression. These issues require a great deal of talk. Now I like a play with a message (see 55 Days or the best of Shaw when he's well done), but Prebble makes the mistake of sacrificing character for issues. The result was one which I have remarked on before and which is usually fatal for me in terms of my view of a piece, apart from one or two fleeting moments I didn't give a damn about any of the people on stage. I would also note that very similar subject matter has been far more effectively treated in the musical Next to Normal which sadly never made it to London.

The performers are nothing to write home about either. They're all perfectly solid, but nothing really leapt out and took me by the throat, though it is only fair to say they aren't helped by the material. Piper and Anastasia Hille as the depressed doctor have moments which do suggest that with a better script they could really shine, but it's not enough to save the evening.

Sunday 16 December 2012

The SCO present two Weber concertos for the price of one

Saturday's concert, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra's last of 2012, is one of those I have been most looking forward to this season. It did not disappoint.

The reason for my interest was the two Weber concertos at its centre. Now, I am not especially a fan of Weber per se, nor do I know either the clarinet or bassoon concertos terribly well. What made this an interesting programme was the presence of two of the SCO's principals as soloists. This is a good prospect for several reasons. First, the orchestra is fortunate to have a number of exceptional players on hand. Indeed, last year when a newspaper waxed lyrical that the Berlin Philharmonic was hands down the best in the world and cited fine solos as evidence, my response (having attended the same series of concerts that prompted the piece) was that if offered the choice I wouldn't swap the SCO principals for theirs. Secondly, and because of this talent, it's nice to see them given the chance to do a little bit more.

Bassoonist Peter Whelan had his turn first. A few years ago we were treated to his reading of the Mozart concerto and he proved himself no less adept with Weber. Whelan has a beautifully rich tone to his playing and that was much in evidence, especially during the slow movement. In the outer movements Weber provided fiendishly rapid runs which were as breathtaking to listen to as one images they were to play, but Whelan was more than a match for them. Beneath him the orchestra, under Pablo Gonzalez, provided well judged accompaniment, never in danger of swamping the soloist but packing ample punch where needed.

The reason for my interest was the two Weber concertos at its centre. Now, I am not especially a fan of Weber per se, nor do I know either the clarinet or bassoon concertos terribly well. What made this an interesting programme was the presence of two of the SCO's principals as soloists. This is a good prospect for several reasons. First, the orchestra is fortunate to have a number of exceptional players on hand. Indeed, last year when a newspaper waxed lyrical that the Berlin Philharmonic was hands down the best in the world and cited fine solos as evidence, my response (having attended the same series of concerts that prompted the piece) was that if offered the choice I wouldn't swap the SCO principals for theirs. Secondly, and because of this talent, it's nice to see them given the chance to do a little bit more.

Bassoonist Peter Whelan had his turn first. A few years ago we were treated to his reading of the Mozart concerto and he proved himself no less adept with Weber. Whelan has a beautifully rich tone to his playing and that was much in evidence, especially during the slow movement. In the outer movements Weber provided fiendishly rapid runs which were as breathtaking to listen to as one images they were to play, but Whelan was more than a match for them. Beneath him the orchestra, under Pablo Gonzalez, provided well judged accompaniment, never in danger of swamping the soloist but packing ample punch where needed.

Meyerbeer's Robert le diable at the Royal, or, A Justified Revival

The opera year in London has ended with both major companies reviving neglected works: Vaughan Williams's The Pilgrim's Progress at English National Opera and Meyerbeer's Robert le diable at the Royal Opera House. Critical reaction to the former was largely positive, to the latter largely negative, and one has a slight sense that one of those critical mood swings is in progress with ENO on the rise after a long period of very justifiable criticism. The distinction in reaction is not in my view justified, and I'll come back to why at the end of the review.

Much to my surprise, I very much enjoyed the Meyerbeer. First of all there's Laurent Pelly's production. The visual colour and the flexible design is wonderfully refreshing – I have sat through far too many eyesore productions this season. Personally I thought the still life horses and knights for the tournament work beautifully (I slightly wondered if Pelly had seen A Knight's Tale), the mountainside that reverses to become the graveyard is a clever bit of flexible set, and the final tableau of Act III with Purgatory suddenly conjured among the graves was especially striking. For a moment or two in Act IV I could see why some critics had complained about the mobile set, but actually the pay-off of that movement creates an effective final image and you've got to do something because one of Meyerbeer's problems is that he's very bad at endings. I've also seen complaints about, I think, Monty Pythonesque knights, but I think a bit of tongue in cheek around the whole enterprise is no bad thing – god help you if you tried to play the thing entirely straight. Also worthy of mention are the effective video designs of Claudio Cavallari. Away from the visuals Pelly also scores with me by being a director who is not frightened of stillness. One of my bugbears is over-fussy movement, and the inability to create telling relations between people through their physical positioning, and Pelly did a good job in both those departments.

The only area which doesn't work is the choreography of Lionel Hoche. There are two issues with this. The cluttered tomb set for Act III Scene 2 looks good but is rather a minefield for the poor dancers making effective variety of movement near impossible to achieve. Within that limitation I just didn't think that Hoche made his zombie nuns debauched enough, although this is another place where Meyerbeer's limits as a composer are shown up.

Much to my surprise, I very much enjoyed the Meyerbeer. First of all there's Laurent Pelly's production. The visual colour and the flexible design is wonderfully refreshing – I have sat through far too many eyesore productions this season. Personally I thought the still life horses and knights for the tournament work beautifully (I slightly wondered if Pelly had seen A Knight's Tale), the mountainside that reverses to become the graveyard is a clever bit of flexible set, and the final tableau of Act III with Purgatory suddenly conjured among the graves was especially striking. For a moment or two in Act IV I could see why some critics had complained about the mobile set, but actually the pay-off of that movement creates an effective final image and you've got to do something because one of Meyerbeer's problems is that he's very bad at endings. I've also seen complaints about, I think, Monty Pythonesque knights, but I think a bit of tongue in cheek around the whole enterprise is no bad thing – god help you if you tried to play the thing entirely straight. Also worthy of mention are the effective video designs of Claudio Cavallari. Away from the visuals Pelly also scores with me by being a director who is not frightened of stillness. One of my bugbears is over-fussy movement, and the inability to create telling relations between people through their physical positioning, and Pelly did a good job in both those departments.

The only area which doesn't work is the choreography of Lionel Hoche. There are two issues with this. The cluttered tomb set for Act III Scene 2 looks good but is rather a minefield for the poor dancers making effective variety of movement near impossible to achieve. Within that limitation I just didn't think that Hoche made his zombie nuns debauched enough, although this is another place where Meyerbeer's limits as a composer are shown up.

Monday 10 December 2012

Opera on Screen - The Met's Un Ballo in Maschera

I dithered about buying a ticket for this. My last try of a cinema relay of classical music was the Berlin Philharmonic performing Bruckner, where I felt that it just wasn't possible to achieve a sufficiently close approximation of the experience of hearing Bruckner live to make it satisfying. I also noticed that this production was directed by David Alden, whose work I do not generally care for. But in the end curiousity got the better of me, plus the fact that I want to support the Lincoln Odeon now that they've decided to bring in the Met Relays for the first time. Overall, I was very glad I went.

The sound worked much better for this than for the Berlin Philharmonic. Clearly you are never going to recreate the precise experience of live performance in a cinema but I actually thought they got pretty near it. There certainly wasn't any moment when I felt the sound was detrimental to my enjoyment of the music. I did wonder if one factor was the screening taking place in one of the small cinemas at the Odeon rather than the vast space we were in for the Berlin concert.

I also take my hat off to the Met's broadcast team. I'm not generally a fan of Deborah Voigt as a singer these days but she makes a good presenter for this – although inevitably some of the singers were more interesting to listen to than others. There was an additional treat in getting to hear Joyce DiDonato rehearsing for Maria Stuarda (to be broadcast in January), and an unintentionally hilarious interview with David Alden in which he insisted on all sorts of things about the production which I have to say were not very apparent to me.

The sound worked much better for this than for the Berlin Philharmonic. Clearly you are never going to recreate the precise experience of live performance in a cinema but I actually thought they got pretty near it. There certainly wasn't any moment when I felt the sound was detrimental to my enjoyment of the music. I did wonder if one factor was the screening taking place in one of the small cinemas at the Odeon rather than the vast space we were in for the Berlin concert.

I also take my hat off to the Met's broadcast team. I'm not generally a fan of Deborah Voigt as a singer these days but she makes a good presenter for this – although inevitably some of the singers were more interesting to listen to than others. There was an additional treat in getting to hear Joyce DiDonato rehearsing for Maria Stuarda (to be broadcast in January), and an unintentionally hilarious interview with David Alden in which he insisted on all sorts of things about the production which I have to say were not very apparent to me.

Monday 3 December 2012

Carmen at ENO, or, God preserve us from mediocrity

The return of Calixto Bieto to the Coliseum is a rather interesting phenomenon. His previous appearances there appeared at the time to contribute to the regrettable sacking of Nicholas Payne. The second of those two appearances, his production of Verdi's A Masked Ball was however the only production of his I've seen which I thought really worked. I also saw several others during the McMaster era in Edinburgh including a very boring version of a Spanish play by the name of Celestina and an unsuccessful relocation of Hamlet to the Palace nightclub. So I bought a ticket for this one mainly because I have developed a certain academic interest in watching the on-going saga of the Berry years.

It also has to be said that to wow me with this particular opera faced other challenges. It isn't a score I'm particularly keen on (this is the first time I've seen it staged in many years of opera going, and I don't think I shall be rushing to see it staged again). Further, I was privileged to hear it performed in Berlin in April by the Berlin Philharmonic under Sir Simon Rattle, and with a cast led by Jonas Kaufmann and Magdalena Kozena. That was an outstanding evening (reviewed here by my esteemed brother). I'm afraid this performance didn't get near it.

Let us start with Bieto's production. This has divided critics into those who've raved and those who've loathed. Last night some debate unfolded on my Twitter timeline after one Telegraph critic announced that he had walked out in the interval. I can't really see any good reason for walking out of this for the simple reason that little of interest happens. In fairness to Bieto there are a couple of nice ideas – the big bull sign which is dismembered during the prelude to Act Four, followed by a bit of make believe bullfighting with the head is clever, and the encircling of Carmen and Jose in a bullring for their final confrontation likewise. But beyond that I found it a boring afternoon. There was little in the way of dramatic tension or erotic heat generated between the various protagonists, and Carmen's escape at the end of Act I was particularly unconvincing. More seriously, Bieto appears to regard all the sex in the show as being rather nasty and seedy. Well, I don't say this isn't a reasonable viewpoint but the problem is that it makes it rather difficult to care about any of the characters. I didn't find Carmen in the lest bit seductive, and couldn't really see why the men were falling over themselves to bed her. There were also the usual bits of incoherent staging – the opening chorus sings about all the people crossing the square – despite the fact that there's nobody else there, and when Escamillo enters in Act Four he comes in behind the chorus although they are apparently watching him out in the auditorium. Generally, I found Bieto's handling of the chorus ineffective.

It also has to be said that to wow me with this particular opera faced other challenges. It isn't a score I'm particularly keen on (this is the first time I've seen it staged in many years of opera going, and I don't think I shall be rushing to see it staged again). Further, I was privileged to hear it performed in Berlin in April by the Berlin Philharmonic under Sir Simon Rattle, and with a cast led by Jonas Kaufmann and Magdalena Kozena. That was an outstanding evening (reviewed here by my esteemed brother). I'm afraid this performance didn't get near it.

Let us start with Bieto's production. This has divided critics into those who've raved and those who've loathed. Last night some debate unfolded on my Twitter timeline after one Telegraph critic announced that he had walked out in the interval. I can't really see any good reason for walking out of this for the simple reason that little of interest happens. In fairness to Bieto there are a couple of nice ideas – the big bull sign which is dismembered during the prelude to Act Four, followed by a bit of make believe bullfighting with the head is clever, and the encircling of Carmen and Jose in a bullring for their final confrontation likewise. But beyond that I found it a boring afternoon. There was little in the way of dramatic tension or erotic heat generated between the various protagonists, and Carmen's escape at the end of Act I was particularly unconvincing. More seriously, Bieto appears to regard all the sex in the show as being rather nasty and seedy. Well, I don't say this isn't a reasonable viewpoint but the problem is that it makes it rather difficult to care about any of the characters. I didn't find Carmen in the lest bit seductive, and couldn't really see why the men were falling over themselves to bed her. There were also the usual bits of incoherent staging – the opening chorus sings about all the people crossing the square – despite the fact that there's nobody else there, and when Escamillo enters in Act Four he comes in behind the chorus although they are apparently watching him out in the auditorium. Generally, I found Bieto's handling of the chorus ineffective.

Thursday 29 November 2012

Great Comics Part II - Rising Stars

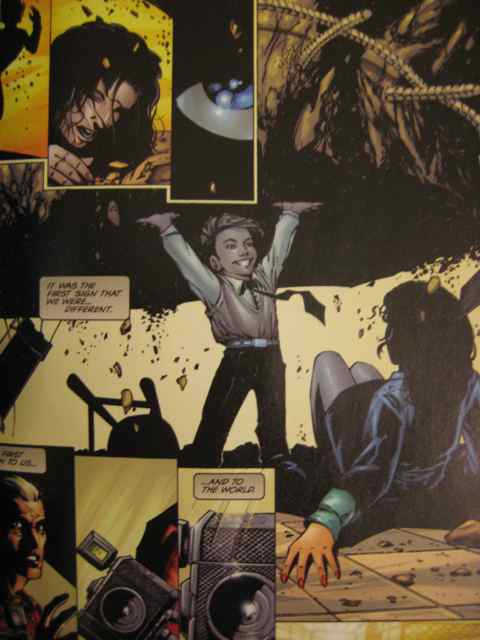

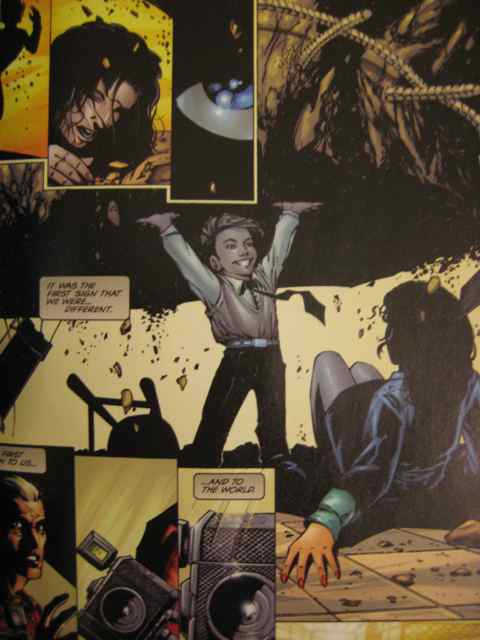

A poorly maintained elementary school ceiling collapses, and at the last moment a young child catches the falling masonry and saves the day.

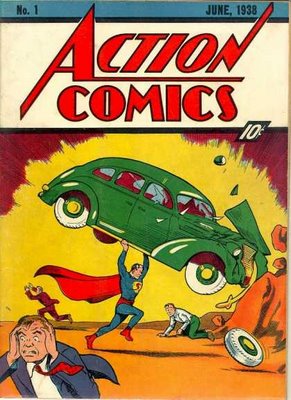

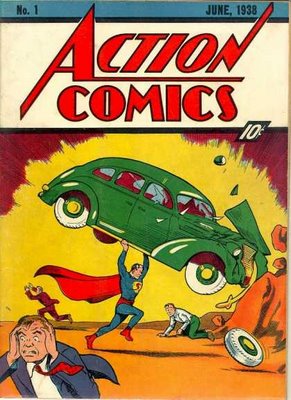

The boy's name is Matthew Bright. It is the first indication that anyone in the town of Pederson, Illinois, is different, or rather special, and it is one of the key images of Joe Straczynski's comic book masterpiece Rising Stars. The image seems to have its roots in the cover of Action Comics #1 (the first appearance of a slightly better known hero by the name of Superman) and it recurs three more times in the story, even once with a car. It defines Bright, one of the story's key characters, and his determination to put the lives of others before his own.

The boy's name is Matthew Bright. It is the first indication that anyone in the town of Pederson, Illinois, is different, or rather special, and it is one of the key images of Joe Straczynski's comic book masterpiece Rising Stars. The image seems to have its roots in the cover of Action Comics #1 (the first appearance of a slightly better known hero by the name of Superman) and it recurs three more times in the story, even once with a car. It defines Bright, one of the story's key characters, and his determination to put the lives of others before his own.

Tuesday 20 November 2012

The chances of anything coming from Mars twice

Next week sees the release of an updated version of Jeff Wayne's musical version of The War of the Worlds. I'm really quite excited about this. The original is tremendous fun; silly, but gloriously so. A new version is therefore to be welcomed, and I look forward to hearing it.

However, it seems that not everyone shares this view (how dull that would be). The Arts Desk featured it as their disc of the day this morning. I was rather surprised to discover that 'disc of the day' was not, apparently, meant as a compliment since they appear to have awarded it a solitary star. Clearly not to the reviewer's taste, then. For me, unless there are major deficiencies in the new cast as compared with the original, one star would be a travesty. But this isn't a post about the album or the show. If you want that, read what our friend and past contributor Andrew Pugsley had to say when it toured in 2010. Nor is this a dig at The Arts Desk. Rather, it is a riff on their subheadline:

Clearly I've been listening to too much More or Less lately, but this got me thinking. What are the chances of anything coming from Mars twice? What follows is a slightly eclectic, more mathematical and frankly very silly departure from our normal fare.

However, it seems that not everyone shares this view (how dull that would be). The Arts Desk featured it as their disc of the day this morning. I was rather surprised to discover that 'disc of the day' was not, apparently, meant as a compliment since they appear to have awarded it a solitary star. Clearly not to the reviewer's taste, then. For me, unless there are major deficiencies in the new cast as compared with the original, one star would be a travesty. But this isn't a post about the album or the show. If you want that, read what our friend and past contributor Andrew Pugsley had to say when it toured in 2010. Nor is this a dig at The Arts Desk. Rather, it is a riff on their subheadline:

The chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one, they said. But twice?

Clearly I've been listening to too much More or Less lately, but this got me thinking. What are the chances of anything coming from Mars twice? What follows is a slightly eclectic, more mathematical and frankly very silly departure from our normal fare.

Sunday 18 November 2012

Steel Pier at the Union, or, The Musical as Parable

Once again the Union Theatre has done musical theatre fans a great service by staging the European premiere of Kander and Ebb's 1997 musical, Steel Pier. While the score of the show is not the duo's finest, this actually isn't a problem. Because really, it struck me as the show drew on, this is almost more a play with music than a classic musical. And in that context, the music does exactly what it needs to do, which is drive forward the relationships between the characters. And the characters are completely compelling.

The story concerns a dance marathon at the aforementioned Steel Pier. As the show begins, Rita Racine (Sarah Galbraith) is waiting for her partner to show up. When he fails to appear she finds herself saddled with daredevil pilot, Bill Kelly (Jay Rincon). To tell you any more would spoil the plot, and this is emphatically a show that benefits from one not knowing in advance how it's going to go (although apparently I discovered afterwards if you've seen the film They Shoot Horses Don't They this may give you some clues). Suffice it to say that it's more than a little Capraesque, that the ending brought tears to my eyes, and the moral seemed to be speaking to me.

Director Paul Taylor Mills has assembled an excellent cast. It's always a big test of a musical like this whether the romantic leads can make you believe, and Galbraith and Rincon pass this test with flying colours. Some will possibly find the scripting of their scenes a bit too melodramatic but they're played with enough sincerity that it works. There's a particularly lovely moment when Rincon says something like “You dance like this and in a moment your whole life can change” which is the kind of line that gets me every time. Aimee Atkinson's Shelby has the show's biggest number - “Everybody's Girl” - and duly brings the house down (this is probably the only time you will ever find me pleased to have been sat in the front row), but she is also moving in the scene where we see behind the mask. Also worthy of particular mention is Lisa-Anne Wood's Precious Maguire who gets impressively more ghastly as scene follows scene. The supporting ensemble execute Richard Jones's impressive choreography with remarkable flair considering the space restrictions. But Jones also has a nicely inventive eye for the smaller moments - like the use of a simple white umbrella in "First You Dream".

The story concerns a dance marathon at the aforementioned Steel Pier. As the show begins, Rita Racine (Sarah Galbraith) is waiting for her partner to show up. When he fails to appear she finds herself saddled with daredevil pilot, Bill Kelly (Jay Rincon). To tell you any more would spoil the plot, and this is emphatically a show that benefits from one not knowing in advance how it's going to go (although apparently I discovered afterwards if you've seen the film They Shoot Horses Don't They this may give you some clues). Suffice it to say that it's more than a little Capraesque, that the ending brought tears to my eyes, and the moral seemed to be speaking to me.

Director Paul Taylor Mills has assembled an excellent cast. It's always a big test of a musical like this whether the romantic leads can make you believe, and Galbraith and Rincon pass this test with flying colours. Some will possibly find the scripting of their scenes a bit too melodramatic but they're played with enough sincerity that it works. There's a particularly lovely moment when Rincon says something like “You dance like this and in a moment your whole life can change” which is the kind of line that gets me every time. Aimee Atkinson's Shelby has the show's biggest number - “Everybody's Girl” - and duly brings the house down (this is probably the only time you will ever find me pleased to have been sat in the front row), but she is also moving in the scene where we see behind the mask. Also worthy of particular mention is Lisa-Anne Wood's Precious Maguire who gets impressively more ghastly as scene follows scene. The supporting ensemble execute Richard Jones's impressive choreography with remarkable flair considering the space restrictions. But Jones also has a nicely inventive eye for the smaller moments - like the use of a simple white umbrella in "First You Dream".

Saturday 17 November 2012

Howard Brenton's 55 Days, or, We are Bound to the Stake and Must Stand the Course

This is the third unmissable show of the year. It is up there with the West End Long Day's Journey into Night and the Chichester Arturo Ui. That is how good it is.

Howard Brenton's materials are superbly dramatic in themselves. He takes us through the 55 days from the purge of Parliament for having voted against trying Charles I through to the sovereign's execution. As we watch, men and women wrestle with a fundamental impossible dilemma. How do you deal with a man who refuses to accept that anybody except God has power to judge him. It really is a case of observing the collision of two diametrically opposed opinions. Cromwell in particular, in this version of history, finds it inconceivable that Charles can actually possibly believe what he says – that no power on earth can judge him. Moreover, Cromwell, unlike Charles, is all too horribly aware of the price the Civil War has exacted from the populace of England. Though we see no battles in this production, the weight of the violence, the tearing of society is very present. As long as the dilemma is unresolved, it is clear things cannot be healed.

This is a profoundly political play. Some may perhaps find it too much so, but I found it completely compelling. It is also a play which has resonance way beyond its immediate subject matter, and as with all such plays which are truly great Brenton has no need to spell it out for us, it is there, unavoidable. Have we really shed the delusions of pageantry and monarchy? Did Cromwell succeed in creating a better order? Two moments among scene after scene that capture these dilemmas really stood out for me. First, when Cromwell asserts passionately that after the trial and execution is done Parliament will be sovereign and men will think it glorious to be citizens of England because of her Parliament. Oh, if it were only so. Second, when one of the commissioners, after the decision is made, praises Cromwell and moves to kiss his hand.

Brenton's text is given powerful life by a magnificent company. At their head is Douglas Henshall's Cromwell. When we first see him he is still one among equals, and slowly, inexorably, he becomes the figure to whom persistently, inescapably, eyes turn for guidance. The genius of Brenton's text and Henshall's performance is to sustain one's belief that Cromwell genuinely does not want that power. Henshall delivers a number of speeches with that command that just holds, but I found especially powerful his description of the Scotch boy rebel staring up at him as at some creature of horror. Mark Gatiss as Charles I has in some ways the harder part to sustain – his arrogance and certainty make him more difficult to sympathise with. Yet this doesn't make his performance any the less compelling, and the trouble is that he does have a point – Cromwell and co. find themselves having to bend the law to gain their ends – as the play goes on the gap between them narrows, and narrows.

Howard Brenton's materials are superbly dramatic in themselves. He takes us through the 55 days from the purge of Parliament for having voted against trying Charles I through to the sovereign's execution. As we watch, men and women wrestle with a fundamental impossible dilemma. How do you deal with a man who refuses to accept that anybody except God has power to judge him. It really is a case of observing the collision of two diametrically opposed opinions. Cromwell in particular, in this version of history, finds it inconceivable that Charles can actually possibly believe what he says – that no power on earth can judge him. Moreover, Cromwell, unlike Charles, is all too horribly aware of the price the Civil War has exacted from the populace of England. Though we see no battles in this production, the weight of the violence, the tearing of society is very present. As long as the dilemma is unresolved, it is clear things cannot be healed.

This is a profoundly political play. Some may perhaps find it too much so, but I found it completely compelling. It is also a play which has resonance way beyond its immediate subject matter, and as with all such plays which are truly great Brenton has no need to spell it out for us, it is there, unavoidable. Have we really shed the delusions of pageantry and monarchy? Did Cromwell succeed in creating a better order? Two moments among scene after scene that capture these dilemmas really stood out for me. First, when Cromwell asserts passionately that after the trial and execution is done Parliament will be sovereign and men will think it glorious to be citizens of England because of her Parliament. Oh, if it were only so. Second, when one of the commissioners, after the decision is made, praises Cromwell and moves to kiss his hand.

Brenton's text is given powerful life by a magnificent company. At their head is Douglas Henshall's Cromwell. When we first see him he is still one among equals, and slowly, inexorably, he becomes the figure to whom persistently, inescapably, eyes turn for guidance. The genius of Brenton's text and Henshall's performance is to sustain one's belief that Cromwell genuinely does not want that power. Henshall delivers a number of speeches with that command that just holds, but I found especially powerful his description of the Scotch boy rebel staring up at him as at some creature of horror. Mark Gatiss as Charles I has in some ways the harder part to sustain – his arrogance and certainty make him more difficult to sympathise with. Yet this doesn't make his performance any the less compelling, and the trouble is that he does have a point – Cromwell and co. find themselves having to bend the law to gain their ends – as the play goes on the gap between them narrows, and narrows.

ENO's Pilgrim's Progress, or Vaughan Williams Fails to Find the Celestial City

I have to begin this review by acknowledging that there are very plainly two viewpoints on this work. There are those who find it a powerfully moving, in many cases deeply spiritual experience. Then there are those, of whom I am one, who do not. Given that there were the usual swathes of empty seats (at least in the Dress Circle) I suspect I am not alone.

The most positive aspect of this performance was the musical performances led by Roland Wood as the Pilgrim. He's not always well served by the direction (when he's armoured up in particular the thing has a rather unfortunate Monty Python air to it) but his diction is excellent, he sings with great character, and has the stamina to carry this challenging role. The various supporting camoes are all well taken, but none of them really have enough time to make a great impression. Of them I especially enjoyed hearing Kitty Whately again, who previously impressed me in Handel with English Touring Opera – though I was fascinated to discover from looking at the programme this morning that she was supposed in one scene to be a woodcutter's boy. Ann Murray also has two nice turns as Madam Bubble and Madam By-Ends. They were ably supported by the conducting of Martyn Brabbins and the singing and playing of the ENO Chorus and Orchestra, all of whom do their best with this problematic score.

About the production I was less convinced. The idea is that Bunyan himself has been imprisoned, imagines his journey to the celestial city, and at the end is back in prison again. Well fair enough. It isn't irritating but I didn't find it very inspired. There was to my mind a lack of a real feeling of a journey. The chorus have some bizarre Selleresque gestural moments. Oh, and big and not terribly effective puppets appear to be in (I couldn't really see why the Pilgrim didn't just dodge round the unmanouvreable Apollyon). The second half generally works less well than the first, the film shots of the First World War trenches didn't really fit, and the arrival in the Celestial City just doesn't come off dramatically.

The most positive aspect of this performance was the musical performances led by Roland Wood as the Pilgrim. He's not always well served by the direction (when he's armoured up in particular the thing has a rather unfortunate Monty Python air to it) but his diction is excellent, he sings with great character, and has the stamina to carry this challenging role. The various supporting camoes are all well taken, but none of them really have enough time to make a great impression. Of them I especially enjoyed hearing Kitty Whately again, who previously impressed me in Handel with English Touring Opera – though I was fascinated to discover from looking at the programme this morning that she was supposed in one scene to be a woodcutter's boy. Ann Murray also has two nice turns as Madam Bubble and Madam By-Ends. They were ably supported by the conducting of Martyn Brabbins and the singing and playing of the ENO Chorus and Orchestra, all of whom do their best with this problematic score.

About the production I was less convinced. The idea is that Bunyan himself has been imprisoned, imagines his journey to the celestial city, and at the end is back in prison again. Well fair enough. It isn't irritating but I didn't find it very inspired. There was to my mind a lack of a real feeling of a journey. The chorus have some bizarre Selleresque gestural moments. Oh, and big and not terribly effective puppets appear to be in (I couldn't really see why the Pilgrim didn't just dodge round the unmanouvreable Apollyon). The second half generally works less well than the first, the film shots of the First World War trenches didn't really fit, and the arrival in the Celestial City just doesn't come off dramatically.

Saturday 20 October 2012

ENO's Julius Caesar, or, Undaunted by Past Disasters the Ship of Berry Sails Blithely On (to Yet Another Reef)

The vast majority of reviews of this production have been poor. But there is little sense from most critics that this is more than an individual flop for the company. To my mind it is symptomatic of the company's ongoing problems of artistic direction. This review will therefore deal both with this particular production, and those wider issues.

I could write a long review about the surface idiocies of this production: the slug, sorry egg, balancers, the de-tonguing of the giraffe, the inexplicable appearance of the garden hose. But this would distract from the central, fatal flaw, which on this showing ought to disqualify Michael Keegan-Doran from any further ventures outside of straight choreography. Keegan-Doran fundamentally appears either incapable of, or to have had no desire to, actually dirct his principal cast. Line after line is rendered ludicrous by their being no attempt to direct the performers in a way to render their interactions dramatically convincing. The direction affords none of the performers any depth – here and there some emotional connection is occasionally salvaged, by dint one suspects of the performers innate musicianship (and in one case real dramatic presence). But it is insufficient to salvage the evening.

The one area where Keegan-Doran's impact is all too evident is the choreography. Choreography married to Handel can make for an exceptional performance – see the current Glyndebourne production of this opera. But not here. Keegan-Doran's dance ensemble basically seem to be in a completely different show from the singers. They add nothing, except irritating distraction, to the evening. It is never clear who these people are, why they are there, or why, given that they are there, they are dancing – there is no dramatic or emotional benefit from their presence at all, and one is driven to the conclusion that Keegan-Doran, being an inexperienced and unconfident director retreated to the world he knows best (compare with Mike Figgis's attempt to direct an opera in the 2010-11 ENO season).

I could write a long review about the surface idiocies of this production: the slug, sorry egg, balancers, the de-tonguing of the giraffe, the inexplicable appearance of the garden hose. But this would distract from the central, fatal flaw, which on this showing ought to disqualify Michael Keegan-Doran from any further ventures outside of straight choreography. Keegan-Doran fundamentally appears either incapable of, or to have had no desire to, actually dirct his principal cast. Line after line is rendered ludicrous by their being no attempt to direct the performers in a way to render their interactions dramatically convincing. The direction affords none of the performers any depth – here and there some emotional connection is occasionally salvaged, by dint one suspects of the performers innate musicianship (and in one case real dramatic presence). But it is insufficient to salvage the evening.

The one area where Keegan-Doran's impact is all too evident is the choreography. Choreography married to Handel can make for an exceptional performance – see the current Glyndebourne production of this opera. But not here. Keegan-Doran's dance ensemble basically seem to be in a completely different show from the singers. They add nothing, except irritating distraction, to the evening. It is never clear who these people are, why they are there, or why, given that they are there, they are dancing – there is no dramatic or emotional benefit from their presence at all, and one is driven to the conclusion that Keegan-Doran, being an inexperienced and unconfident director retreated to the world he knows best (compare with Mike Figgis's attempt to direct an opera in the 2010-11 ENO season).

Sunday 14 October 2012

King Lear at the Almeida, or, The Star's In Place But Not Much Else

Back at the tail end of last year I had this down as one of the shows I was most looking forward to in 2012, but I'm afraid this is a show that just doesn't live up to its advance prospects, for all sorts of reasons.

The first big problem is the design where Tom Scutt seems to have come over all Christopher Marthaler. This is the dullest thing to look at for three hours since the dreadful Bayreuth Tristan. The stage is basically bare for the entire show – apart from occasional pieces of furniture and the enormous and as far as I could see wholly pointless dead fox strung up at the back at one point in Act One. There is really no meaningful attempt to locate the action anywhere concrete – beyond some kind of ruined castle at some undetermined point. Scutt claims in his programme notes that “If you try and pin it [Lear] down or set it too tightly in a time and a place, it kicks like a mule.” Frankly, I wish it had kicked him harder.

If you're going to drain away the feeling of concrete and differentiated places from a production then you have to be able to replace them with more than usually effective management of your ensemble. They are going to have to create the world by speech and movement which the production has decided not to attempt. Unfortunately Michael Attenborough's direction falls down here. There's a sad lack of those crucial moments of tension that make truly great theatre. Indeed, one almost feels after a while as if one is watching old style stand and deliver. Moments in the second half when, for example, Goneril is being affectionate with Edmund, stand out starkly because there's not enough of such loaded physical connection elsewhere in the performance. The rare occasions when clear direction is in evidence tend to the bizarre. Other critics have commented that Attenborough's idea seems to be that Lear has sexually abused his elder daughters. This is brought out in one or two places but nowhere near consistently enough to make it work. In any case I am far from convinced that this is a viable interpretation – I find it difficult to see how we can sympathise with Lear as we really need to as the play goes on, if he has committed so vile a crime – and indeed one further wonders given that implication why Cordelia dotes on him. In short, on this showing at any rate, it is an interpretation that does too much violence to other parts of the text with not enough return from the places that it does illuminate. Elsewhere I felt too often that the text was passing Attenborough by – for example that marvellous moment when the Fool replays the “Nothing will come of Nothing” exchange which seems to me the point when Lear begins to recognise his folly goes for nothing in this staging.

The first big problem is the design where Tom Scutt seems to have come over all Christopher Marthaler. This is the dullest thing to look at for three hours since the dreadful Bayreuth Tristan. The stage is basically bare for the entire show – apart from occasional pieces of furniture and the enormous and as far as I could see wholly pointless dead fox strung up at the back at one point in Act One. There is really no meaningful attempt to locate the action anywhere concrete – beyond some kind of ruined castle at some undetermined point. Scutt claims in his programme notes that “If you try and pin it [Lear] down or set it too tightly in a time and a place, it kicks like a mule.” Frankly, I wish it had kicked him harder.

If you're going to drain away the feeling of concrete and differentiated places from a production then you have to be able to replace them with more than usually effective management of your ensemble. They are going to have to create the world by speech and movement which the production has decided not to attempt. Unfortunately Michael Attenborough's direction falls down here. There's a sad lack of those crucial moments of tension that make truly great theatre. Indeed, one almost feels after a while as if one is watching old style stand and deliver. Moments in the second half when, for example, Goneril is being affectionate with Edmund, stand out starkly because there's not enough of such loaded physical connection elsewhere in the performance. The rare occasions when clear direction is in evidence tend to the bizarre. Other critics have commented that Attenborough's idea seems to be that Lear has sexually abused his elder daughters. This is brought out in one or two places but nowhere near consistently enough to make it work. In any case I am far from convinced that this is a viable interpretation – I find it difficult to see how we can sympathise with Lear as we really need to as the play goes on, if he has committed so vile a crime – and indeed one further wonders given that implication why Cordelia dotes on him. In short, on this showing at any rate, it is an interpretation that does too much violence to other parts of the text with not enough return from the places that it does illuminate. Elsewhere I felt too often that the text was passing Attenborough by – for example that marvellous moment when the Fool replays the “Nothing will come of Nothing” exchange which seems to me the point when Lear begins to recognise his folly goes for nothing in this staging.

Call Me Madam at the Union, or, Just Not Quite Enough Stars

As I can't be whole-heartedly enthusiastic about this revival, let me start with a word of praise for the Union's upcoming schedule, which like so much non-West End stuff seems to get little notice in the mainstream press or indeed elsewhere in the blogosphere. I only hope fellow musical theatre afficionados are paying attention. Coming up there in the next three months we have Kander and Ebb's Steel Pier and Mary Rodgers's Once Upon a Mattress – I can't recall either having been staged in London in my memory, though doubtless somebody will correct me. Whatever else you do in the next few months, if you're a musical theatre fan, give the tiresome long-running nonsense in the West End a miss and head out to Southwark.

On balance you should also head out there for the venue's current production of Irving Berlin's Call Me Madam. You may know this from the film version which stars Ethel Merman (who originated the role of Mrs Sally Adams on stage) and the incomparable Donald O'Connor (better known as Cosmo in Singin' in the Rain). My recollection of the film was of a patchy experience made by the stars rather than the show, and on the whole the same is true of this production – except that it just hasn't got quite enough stars to achieve the same effect.

The best thing in this performance is Lucy Williamson's performance in the Ethel Merman part. Williamson's particular brilliance in this show is that she manages at pretty much every turn to transcend its limitations. There are little bits of business – gestures, expressions, asides which go to make up a great characterisation. She draws the eye when she's onstage and is consistently funny to watch. If Williamson were on stage the whole time the show would be pretty triumphant. Unfortunately she isn't.

On balance you should also head out there for the venue's current production of Irving Berlin's Call Me Madam. You may know this from the film version which stars Ethel Merman (who originated the role of Mrs Sally Adams on stage) and the incomparable Donald O'Connor (better known as Cosmo in Singin' in the Rain). My recollection of the film was of a patchy experience made by the stars rather than the show, and on the whole the same is true of this production – except that it just hasn't got quite enough stars to achieve the same effect.

The best thing in this performance is Lucy Williamson's performance in the Ethel Merman part. Williamson's particular brilliance in this show is that she manages at pretty much every turn to transcend its limitations. There are little bits of business – gestures, expressions, asides which go to make up a great characterisation. She draws the eye when she's onstage and is consistently funny to watch. If Williamson were on stage the whole time the show would be pretty triumphant. Unfortunately she isn't.

Sunday 26 August 2012

EIF 2012 – The Rape of Lucrece, or, I'll Tell Thee a Tale to Bind Thee

This was my last International Festival drama for this year, and by goodness it was a marvellous way to finish. After one too many over elaborate and dull nonsenses, this performance is a reminder that to create great theatre you don't need more than a fine text (Shakespeare's Rape of Lucrece) and a world class singing actress (Camille O'Sullivan).

O'Sullivan like Barry McGovern in Watt knows the dynamic of story telling. At the beginning she has that quiet authority of the great narrator leading you into the labyrinth. She has the art of voice and gesture which means that throughout the story even though the stage is basically bare you really feel that you see the defiled bed, the hapless Lucrece, the lust filled Tarquin. She switches effortlessly from the outside authority to the three principal characters of Lucrece, Tarquin and Lucretius (Lucrece's despairing father who has a powerful speech towards the close). She also makes you feel the weight of fate – the balance in the story that on some level longs to hold back the disaster and knows that it must come.

The story is delivered in a mixture of speech and song which I found wholly compelling and very moving. But I think the heart of O'Sullivan's achievement is that she can really deliver Shakespeare – this is far more difficult and far less common than you might imagine. But O'Sullivan really knows how to make the phrases live, she is consistently spot on with which words to give weight to, which phrases to linger on.

EIF 2012 – A Midsummer Night's Dream (As You Like It), or, Theatre Like a Broken Pencil (2)

As I descended the stairs of the Kings Theatre after this tedious matinee I heard a fellow audience member describe this show as a Russian Revolution. The temptation to utter a sharp retort was exceedingly strong, but I resisted. There is nothing revolutionary about this show. It is another tedious exposition of many tired cliches of the modern theatre director which have previously been more than sufficiently exhibited in other offerings of the International Festival's Drama programme.

Director Dmitry Krymov follows in the footsteps of Silviu Purcarete. Like Purcarete with Swift, Krymov appears for reasons not wholly clear to be unable to face staging Shakespeare's play complete. He therefore resorts to an alternative we have often seen before – he'll attempt only a small section of the whole. The section Krymov has chosen is the Mechanicals play. In the Shakespeare I shouldn't think this can last more than half an hour, in Krymov's hands it is elongated to an hour and forty minutes. You may possibly be thinking that there cannot be enough material in the Mechanicals play to sustain such an extension and you would be absolutely right.

This is even more the case because Krymov is not in fact interested in delivering much of Shakespeare's text at all – vast swathes of this play are textless, with occasional interventions from the Duke's court (ranged along the side of the extended stage and in the boxes) who don't succeed in being funnier than their Shakespearean counterparts who were not terribly funny to start with.

EIF 2012 – Les Nuafrages du Fol Espoir (Aurores), or Much That Is Stunning But There Remains a But

Before I start in on this review I must be very clear. Unless Mills can afford to invite Mnouchkine back again you are unlikely to see anything like this in the UK again in a hurry. I unequivocally urge you to get a ticket if you can and experience it despite the overall reservations I shall make in the course of this review about the show. This justifies the trek to Ingliston as neither of Mills's other two shows there have done.

This show takes place on a vast stage which is visually very striking. We are in an enormous rooftop space above a restaurant somewhere in Paris (I think) on the eve of the First World War. Sets manouvred by the cast appear and disappear from the rooms off stage and from the rear curtained off portion of the main area. In the centre a complex system of pulleys and counterweights is constantly in use to suspend surtitle screen, actors and other elements of the design. The attention to detail in the visuals throughout this epic recalled to my mind some of the lavish toys from the film of that name, and the theatre as constructed in Moulin Rouge. But these aren't things I can recall ever seeing on a British stage.

The conceit of the show is that filmmakers who have walked out of the leading French company have taken over this space to make a film based on an unpublished Jules Verne novel Les Nuafrages du Fol Espoir. Although the programme argues that the making of nine silent film episodes is interpolated within the overall story of the making of the film in practice the piece is dominated by those filmmaking episodes and they are much the strongest element. The brilliancy of their evocation – shipwrecks, howling wastelands, falling snow, birds, men rowing small canoes across the stage – cannot really be described in prose but has to be witnessed. It is unquestionably a magnificent achievement.

Tuesday 21 August 2012

EIF 2012 – Villa+Discurso, or, A Glass Half Full Evening

The first half of this evening's double bill is an excellent piece of theatre. Three women debate what should be done with the villa of the title where torturing and killing took place under the Pinochet dictatorship. Certain aspects of the piece could so easily lead it into the kind of desiccated territory inhabited by some of the deconstructionist theatre showcased elsewhere in this year's festival – most notably the fact that the three characters are to an extent denied individuality. They are all called Alejandra, what backstory we do learn about them (up until the final moments) is often subsequently called into question. But their doubtful characters, the question mark over their individuality does not end up lessening their humanity and crucially does not stop them from engaging the audience's emotions – or at least did not prevent my emotions from being engaged.

The play is also concerned with a large theme – how do you come to terms with this legacy of torture, of death. But it doesn't get sunk by that theme – rather it is by turns both solemn and playful. There are several set pieces of real poetry as the women defend particular positions – should the Villa be re-created exactly as it was, should it be turned into a museum? But there is also a wonderful self mocking section which points out that everybody who comes there will interpret it differently – laugh at it, cry etc. It's also a gentle mockery of writing a play about it but done with a wit that similar interludes such as Marthaler's completely lacked.

Above all, the play is a reminder that even with this awful legacy so forcefully before them humans do not necessarily become better people. The three women are met in committee because the larger group in charge of the project have failed to reach agreement. Pretty soon these three are also at daggers drawn, there are unpleasant attempts at manipulation, even momentary flare ups of violence. The gulf between the women and the world whose remembrance they are grappling with proves not to be as wide as one might wish to imagine.

Monday 20 August 2012

EIF 2012 – David et Jonathas, or, A Surprisingly Moving Evening

Regular readers will know that I do have a prejudice as a reviewer. Well actually I probably have a number of prejudices but there is one thing I care about more than anything else. I want a performance to engage my emotions. I want to care. For this reason I have even got more out of shows that have made me violently angry than shows in which I have simply been bored (neither of which circumstances I hasten to add applied to this one). I did not expect to be moved by this evening's opera, Charpentier's little known David et Jonathas. I don't usually care for music of that vintage and I booked with my completionist hat on rather than out of a strong desire to see the piece. Yet, as the evening drew on, and as I conquered my initial attack of exhaustion (brought on by yesterday's late night jaunt up Arthur's Seat) I found the work increasingly powerful.

The plot is Biblical and somewhat muddled but the main things you need to know are that Saul is jealous of David and will indeed end up being replaced by him, and David and Jonathas (Saul's son) are in love, and it will all end badly.

The staging, by Andreas Homoki is a bit uneven. The set is basically a confined wooden box which can be broken up into several rooms, and with moveable walls to adjust the spaces with psychological implications for different characters which are clearer at some points than others. The movement of walls is not unreminiscent of some of Christoph Loy's recent productions (and the bits of business with chairs reminded of Marthaler) – clearly these are in elements in current European opera production, but fortunately neither are irritatingly distracting. Homoki's management of his cast is also uneven. There are some very effective images – for example at the height of Saul's torment he finds himself surrounded by images of his wife – but equally tension in staging and movement is often allowed to dissipate. But when Homoki is at his best he really nails it – the moments following Jonathas's death, and the hollowness of the crowning of David are spot on.

The plot is Biblical and somewhat muddled but the main things you need to know are that Saul is jealous of David and will indeed end up being replaced by him, and David and Jonathas (Saul's son) are in love, and it will all end badly.

The staging, by Andreas Homoki is a bit uneven. The set is basically a confined wooden box which can be broken up into several rooms, and with moveable walls to adjust the spaces with psychological implications for different characters which are clearer at some points than others. The movement of walls is not unreminiscent of some of Christoph Loy's recent productions (and the bits of business with chairs reminded of Marthaler) – clearly these are in elements in current European opera production, but fortunately neither are irritatingly distracting. Homoki's management of his cast is also uneven. There are some very effective images – for example at the height of Saul's torment he finds himself surrounded by images of his wife – but equally tension in staging and movement is often allowed to dissipate. But when Homoki is at his best he really nails it – the moments following Jonathas's death, and the hollowness of the crowning of David are spot on.

EIF 2012 - Gergiev and the LSO's Brahms and Szymanowski residence

This four concert series was one of the longer festival residences I can remember. In the past, it has sometimes been the case that after such a sustained exposure to a single group of artists one can tire of them. So it is pleasing to report that after four consecutive nights of Valery Gergiev and the London Symphony Orchestra surveying the symphonies of Brahms and Szymanowski, as well as the concertos of the latter, such fatigue was not in evidence.

Brahms and Szymanowski were perhaps not the most obvious pairing, and even after the cycle they remain so. That is not to say the two composers sat together uneasily, in general the programmes fitted well, but rather that their combined presence didn't appear to offer great insight into each other's works.

Going into the cycle, I had misgivings about the Brahms. While I admire much of his work, I do not always get on with Gergiev's interpretations. For example, although it is well regarded in some quarters, I cannot stand his Mahler. Fortunately, such concerns were largely misplaced. This was helped to a great extent by the exceptional playing of the LSO. I fear in the past I have not rated them quite as highly as they deserve, though this is because I normally hear them in the horribly unflattering acoustic of the Barbican. In the Usher Hall, the quality of their string sound was really a treat, especially when playing at fully strength. The same must be said of the winds, and these performances brought out many details in Brahms' writing for them more clearly than I've noticed before. Indeed, technically speaking, over four nights there was little to fault in the whole orchestra.

Brahms and Szymanowski were perhaps not the most obvious pairing, and even after the cycle they remain so. That is not to say the two composers sat together uneasily, in general the programmes fitted well, but rather that their combined presence didn't appear to offer great insight into each other's works.

Going into the cycle, I had misgivings about the Brahms. While I admire much of his work, I do not always get on with Gergiev's interpretations. For example, although it is well regarded in some quarters, I cannot stand his Mahler. Fortunately, such concerns were largely misplaced. This was helped to a great extent by the exceptional playing of the LSO. I fear in the past I have not rated them quite as highly as they deserve, though this is because I normally hear them in the horribly unflattering acoustic of the Barbican. In the Usher Hall, the quality of their string sound was really a treat, especially when playing at fully strength. The same must be said of the winds, and these performances brought out many details in Brahms' writing for them more clearly than I've noticed before. Indeed, technically speaking, over four nights there was little to fault in the whole orchestra.

EIF 2012 - Gulliver's Travels, or, In Which the Clothes Are Once Again Insufficient For the Emperor

This latest loose version of a classic text offers something of an advance over Meine faire Dame. It has at least got something to substitute for the character and narrative which it has, in the typical manner of the modern European theatre director, decided to dispense with. In fact it has about 45 minutes worth of substitute material. Unfortunately this show lasts for an hour and a half.

Director Silviu Purcarete is also refreshingly, almost amusingly honest about his approach. One of the early images (after a horse has been led round the stage – an animal presence which is justified in the final image but not here) is of a man clearly intended to be Swift/Gulliver being knocked out by a company member, and the book from which he is about to read ripped to shreds. No one can say that Purcarete has not made his intentions clear.

Pucarete then picks a single aspect of Swift's book – the concept of the Yahoos and spends the rest of the show indicating that man is a brutish unpleasant beast through a series of tableaux. Some of this is very visually striking – especially the shadowplay, and the chorus acting as miniatures being played with by a human. But nearly all the episodes (especially the final one which is rather sub Einstein on the Beach) outstay their welcome, and there is too much hanging around between them. Above all, they have nothing to say beyond repeating the basic point, which is why I suggest that the whole thing would have been much stronger condensed to about half the length.

Director Silviu Purcarete is also refreshingly, almost amusingly honest about his approach. One of the early images (after a horse has been led round the stage – an animal presence which is justified in the final image but not here) is of a man clearly intended to be Swift/Gulliver being knocked out by a company member, and the book from which he is about to read ripped to shreds. No one can say that Purcarete has not made his intentions clear.

Pucarete then picks a single aspect of Swift's book – the concept of the Yahoos and spends the rest of the show indicating that man is a brutish unpleasant beast through a series of tableaux. Some of this is very visually striking – especially the shadowplay, and the chorus acting as miniatures being played with by a human. But nearly all the episodes (especially the final one which is rather sub Einstein on the Beach) outstay their welcome, and there is too much hanging around between them. Above all, they have nothing to say beyond repeating the basic point, which is why I suggest that the whole thing would have been much stronger condensed to about half the length.

Wednesday 15 August 2012

EIF 2012 – Meine faire Dame, or Theatre Like a Broken Pencil

Let us start with the positives. There were some funny moments. Some of the music was well sung. The performers themselves can't be faulted. But overall this was dull, over-long and self indulgent. It was, in short, a classic example of deconstruction theatre.

The EIF programme note may lead you to believe that this is going to be a deconstruction of My Fair Lady. This material lasts Christoph Marthaler for about half of this two hour show. To fill up the rest he turns to among other things bits of Lohengrin, The Magic Flute, various pop songs and, I think, Lottie in Weimar. You may wonder how these elements fit together. The answer is that they don't really.

Each episode (for this is largely a show of episodes) outstays its welcome. Some moments (the girl with a problem getting down the stairs for instance) could be really funny but are run over and over again until the life has been sucked out of them. The overall effect is typical of this kind of deconstruction theatre. No meaningful relationships are created between the characters, in the audience I was left feeling emotionally cold.

The EIF programme note may lead you to believe that this is going to be a deconstruction of My Fair Lady. This material lasts Christoph Marthaler for about half of this two hour show. To fill up the rest he turns to among other things bits of Lohengrin, The Magic Flute, various pop songs and, I think, Lottie in Weimar. You may wonder how these elements fit together. The answer is that they don't really.

Each episode (for this is largely a show of episodes) outstays its welcome. Some moments (the girl with a problem getting down the stairs for instance) could be really funny but are run over and over again until the life has been sucked out of them. The overall effect is typical of this kind of deconstruction theatre. No meaningful relationships are created between the characters, in the audience I was left feeling emotionally cold.

EIF 2012 – 2008: Macbeth, or Every Cliché in the Reinvented Classics Book and All to No Avail

Regular readers may recall that one of the first crims in my staging failures book is dullness. I take my hat off to this production – it uses every cliché in the Reinvented Classics book and yet most of it ends up being pretty boring.

Before we get to the various sillinesses (like the inexplicable rabbit and magician) let us begin with the far more fundamental problem. Delivery of the text in this production is diabolical. It's not quite so infuriatingly slow as in the legendary American Repertory Theatre Three Sisters but it is a damn close run thing. There is also the bizarre additional issue that the company seems to believe that doing silly voices or other vocal effects (the version of “Sir, Yes, Sir” became especially annoying) is dramatically effective in itself. It isn't. Pretty rapidly I ceased to believe a word anybody was saying and consequently to give a damn about any of the protagonists.

The staging is proof that you can throw shedloads of money at a production to no good effect. It consists of an architecturally muddled house of four rooms. We may possibly be somewhere in the Middle East but this is never established with any conviction. Scenes take place across the four rooms and a couple of balconies with little evident reason as to why they do so. Creation of effective tension between performers through movement and stillness (in other words basic stagecraft) is depressingly thin. The various explosions and gunfire, impressive in themselves though the former in particular were, in practice did little than to momentarily arouse me from the torpor into which the rest of this tedious performance was dragging me.

Before we get to the various sillinesses (like the inexplicable rabbit and magician) let us begin with the far more fundamental problem. Delivery of the text in this production is diabolical. It's not quite so infuriatingly slow as in the legendary American Repertory Theatre Three Sisters but it is a damn close run thing. There is also the bizarre additional issue that the company seems to believe that doing silly voices or other vocal effects (the version of “Sir, Yes, Sir” became especially annoying) is dramatically effective in itself. It isn't. Pretty rapidly I ceased to believe a word anybody was saying and consequently to give a damn about any of the protagonists.

The staging is proof that you can throw shedloads of money at a production to no good effect. It consists of an architecturally muddled house of four rooms. We may possibly be somewhere in the Middle East but this is never established with any conviction. Scenes take place across the four rooms and a couple of balconies with little evident reason as to why they do so. Creation of effective tension between performers through movement and stillness (in other words basic stagecraft) is depressingly thin. The various explosions and gunfire, impressive in themselves though the former in particular were, in practice did little than to momentarily arouse me from the torpor into which the rest of this tedious performance was dragging me.

EIF 2012 – Samuel Beckett's Watt, or, A Brief Report of a Little Gem

This show is proof of a remark I have made before that very often simple is best. It consists of what I suppose one could call edited highlights of Samuel Beckett's novel Watt performed by Barry McGovern on an almost bare Royal Lyceum stage.

The novel tells the tale of Watt, his journey by train to the house of Mr Knott where he is to work, his life there and his eventual departure. Much of the pleasure is derived simply from Beckett's tongue twisting word games which McGovern brings off with real dexterity helped by his voice being one which I could listen to for hours.

For much of the show it feels funny, and inconsequential. But as the show reaches its conclusion one realises the story actually has a moving depth, and a lot to say beneath the word games about fundamental human dilemmas.

Sadly the run has ended so I can't urge you to catch this, but those outside Edinburgh should look out for future touring performances.

The novel tells the tale of Watt, his journey by train to the house of Mr Knott where he is to work, his life there and his eventual departure. Much of the pleasure is derived simply from Beckett's tongue twisting word games which McGovern brings off with real dexterity helped by his voice being one which I could listen to for hours.

For much of the show it feels funny, and inconsequential. But as the show reaches its conclusion one realises the story actually has a moving depth, and a lot to say beneath the word games about fundamental human dilemmas.

Sadly the run has ended so I can't urge you to catch this, but those outside Edinburgh should look out for future touring performances.

Tuesday 14 August 2012

EIF 2012 – In Which First Music then a Musician Fail to Convince Me

Two brief reports follow on performances which for different reasons just didn't carry me off.

Greyfriars – His Majesty's Sagbutts and Cornetts and Concerto Palatino

Early Music has been a regular feature of the International Festival during Jonathan Mills's directorship. Generally speaking this is not an era of classical music that does much for me and I have consequently not attended many of the concerts in this strand over the last few years. However, I've always been intrigued by the idea of an ensemble of Sagbutts and Cornetts so I decided to give this performance a try.

The concert celebrated the 400th anniversary the day before of the death of Giovanni Gabrieli with an hour long selection of his instrumental pieces featuring various combinations of sackbut (the predecessor of the trombone) and cornetts – described in the programme note as “made of wood [with] finger-holes (like a woodwind instrument) but [using] the cup mouthpiece more often associated with brass ones.” The selections were taken from three collections of Gabrieli's music – the Symphoniae sacrae (1597), the Canzoni per sonare (1608) and the posthumously published Canzone e sonate (1615).

The quality of the playing was excellent and I found more to interest me in the pieces of later date which sounded more complex musically to my unfamiliar ears. That said an hour of this sound world was quite sufficient for me. I'm interested to have heard these performers once but I don't feel I need to hurry to hear them again. This is not a comment on them, but on myself – it rather proved to me that early music is just not really my cup of tea.

Greyfriars – His Majesty's Sagbutts and Cornetts and Concerto Palatino