The Royal Scottish National Orchestra haven't quite unveiled their new season and, in such circumstances, I would normally be a little reticent about stealing their thunder. However, since someone else has already done so, and the information is available for all to see on the Glasgow Concert Halls website (my thanks to @fergusmacleod for the tip), I don't feel too guilty. (Indeed, as I type these words, I receive a message from them absolving me of any such guilt, so no need to wrestle with any moral dilemma over whether or not to publish after all.)

Caveat - the Usher Hall have failed to jump the gun in a similar manner, so this preview applies to Glasgow only and I cannot say which of these concerts will be repeated elsewhere.

The season kicks off at the end of September with Denève and Dvorák's New World symphony, the same one we'll have heard a month earlier from Runnicles and the BBC Scottish at the Edinburgh festival. The programme also includes Ravel's concerto for left hand with Nicholas Angelich as the soloist and MacMillan's Three Interludes from The Sacrifice. Indeed, you could be forgiven for thinking the RSNO are deliberately extending the festival's New Worlds theme as in December we get Postcards from the Americas, featuring Copland, Bernstein, Shilkret (a Trombone concerto no less - this I have to hear) and Ginastera.

The New World symphony appears to tie into two of the seasons themes: Great Symphonies and Great Concertos (it seems perhaps churlish to note that such themes could describe pretty much any orchestral seasons anywhere). Later, in November, Denève is back with the Symphony Fantastique. This should be good: Denève has a good track record in Berlioz, and is always his best with extravagant and dramatic pieces. To make the concert even more attractive, Frank Peter Zimmermann will be playing Szymanowski's 2nd violin concert (bringing back memories of his 2006 visit with the Berlin Philharmonic to play the first).

Tuesday 30 March 2010

Runnicles speaks to Where's Runnicles

A little unbelievably, today marks the third birthday of Where's Runnicles. What better then, by way of a birthday present, than the following article, describing my recent attendance at a BBC SSO rehearsal and subsequent interview with the man himself. And, more excitingly still, the launch of the Where's Runnicles podcast.

I'm sitting in row J of the stalls, in the Usher Hall, one seat in from the aisle in the left hand block. In truth, though, I could be sitting anywhere because the auditorium is all but deserted, but then concert doesn't start for a few more hours. From the stage above, the rich textures of Richard Strauss's songs are emanating from the instruments of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. I'm not watching them though, instead, my head is buried in my notebook as I jot down a few witty comments the maestro has just made.

Suddenly there is there a loud crash. Nothing has gone wrong. The instruments continue to play, but Donald Runnicles has leapt down from the stage and is now strolling past me, up the aisle, to get a proper idea of how Christine Brewer's voice is balancing throughout the hall. It has to be just right and the Usher Hall has a very different acoustic to the equally wonderful City Halls or Music Hall in Aberdeen where they have already performed this programme.

The episode is preceded by the exchange I was noting. Runnicles had remarked to the effect he wished Brewer could hear herself in the auditorium. This in turn led him to recount the faint praise a conductor can give to a singer who has not performed well:

Of course, he quickly assures Brewer that none would ever apply to her. Certainly they wouldn't. Still, it is remarkable to watch them play, following the leader in the absence of the conductor. Had I taken it, it might have been a perfect Where's Runnicles? picture. Some might, at this point, wonder whether this means a conductor is utterly superfluous, given how fine they still sounded. Not so.

I'm sitting in row J of the stalls, in the Usher Hall, one seat in from the aisle in the left hand block. In truth, though, I could be sitting anywhere because the auditorium is all but deserted, but then concert doesn't start for a few more hours. From the stage above, the rich textures of Richard Strauss's songs are emanating from the instruments of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. I'm not watching them though, instead, my head is buried in my notebook as I jot down a few witty comments the maestro has just made.

Suddenly there is there a loud crash. Nothing has gone wrong. The instruments continue to play, but Donald Runnicles has leapt down from the stage and is now strolling past me, up the aisle, to get a proper idea of how Christine Brewer's voice is balancing throughout the hall. It has to be just right and the Usher Hall has a very different acoustic to the equally wonderful City Halls or Music Hall in Aberdeen where they have already performed this programme.

The episode is preceded by the exchange I was noting. Runnicles had remarked to the effect he wished Brewer could hear herself in the auditorium. This in turn led him to recount the faint praise a conductor can give to a singer who has not performed well:

Fabulous isn't the wordI've never heard it sung like that

And, of course, the one that's brought these to mind:

You should have been in the audience

Of course, he quickly assures Brewer that none would ever apply to her. Certainly they wouldn't. Still, it is remarkable to watch them play, following the leader in the absence of the conductor. Had I taken it, it might have been a perfect Where's Runnicles? picture. Some might, at this point, wonder whether this means a conductor is utterly superfluous, given how fine they still sounded. Not so.

Monday 29 March 2010

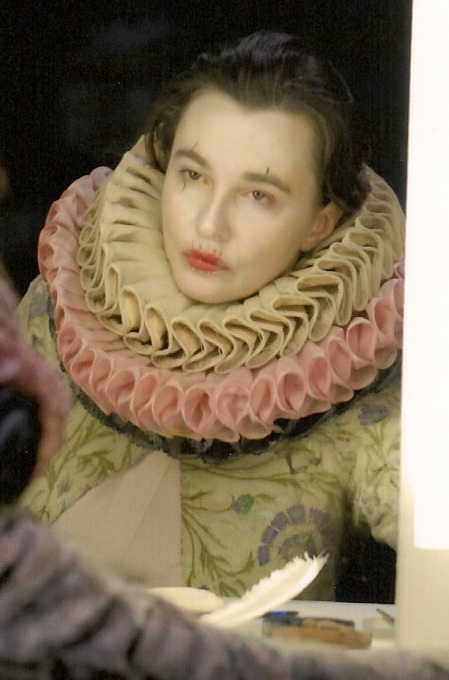

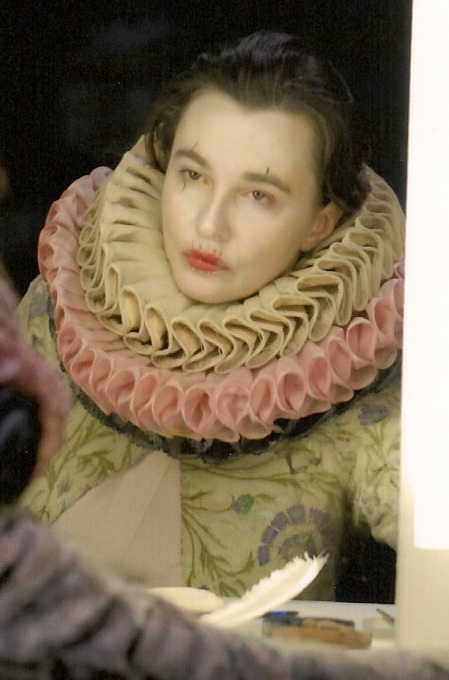

Film review - Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland 3D, dir. Tim Burton, Walt Disney Pictures, cert. PG, on general release.

Alice in Wonderland 3D, dir. Tim Burton, Walt Disney Pictures, cert. PG, on general release.Alice in Wonderland feels like a film made by one of its own characters: amiably quirky, visually splendid and unusual, but characterised by naivety and some very eccentric choices. Oddest and most ill-advised of all of director Tim Burton’s decisions has to be his attempt to position the film as neither an adaptation nor continuation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories, but as an uneasy halfway house, a sequel that doesn’t know that it’s a sequel. The adventures from Carroll’s books are dismissed in the opening scenes of the film as nightmares experienced by the young Alice. Then sixteen years later, running away from her engagement party, she finds herself once again in Wonderland. We’re then treated to a mix of scenes straight from the original (the whole drink me/eat me episode is lifted more or less directly from the page) and a new plot based around Carroll’s nonsense poem Jaberwocky. It makes for a bit of a mess, and the resulting structure is lacking in any tension whatsoever; we have ninety minutes of being asked ‘Can Alice rise to the challenge’ and ‘Were those dreams real?’ before we discover – who’d have thought it? - that yes, Alice can rise to the challenge and those dreams were real after all.

Coupled with this narrative tedium is the unfortunate truth that this Alice (Mia Wasikowska) is simply not an interesting character. Actually, simply is the operative word, since in an effort to preserve the naive curiosity of Carroll’s books, Burton has created a 19-year-old character who acts with the intelligence of a slow 10-year-old. When her mother complains of having only white flowers, Alice’s suggestion that she paint them red is meant to be a charming reference to the Queen of Hearts doing just this in the source material, but instead it just hints at a troubling history of mental retardation. Consequently, it’s hard to really care about her predictable journey of self-discovery.

Dvořák, Shostakovich, Brahms and fireworks from Bychkov, Matsuev and the LSO

Semyon Bychkov has already impressed me with his handling of last year's revival of the Royal Opera House's Don Carlos, so his debut with the London Symphony Orchestra was one of the concerts that jumped out at me when I was doing my last bit of booking back in December. Just as well.

He opened his programme with Dvořák's Carnival Overture. While I'm a big fan of Dvořák, this isn't a piece that's ever especially grabbed me before and hence not one I know all that well. From the opening bars I began to wonder why. Bychkov unleashed the LSO in a phenomenal display of energy and precision. It made for a real party piece, full of orchestral fireworks, and an excellent curtain raiser.

After a brief pause while the piano was raised up through the floor (an always fun to watch quirk of the Barbican - much more interesting than just having it pushed on from the back of the stage), Denis Matsuev joined them for Shostakovich's 2nd piano concerto. He proved every bit the match to Bychkov and the LSO. He maintained clarity through some rapid and intricate passages and found all the necessary weight without recourse to thumping the keyboard. Beneath him, Bychkov balanced his forces well, ensuring the pianist wasn't overwhelmed by the comparatively large orchestra. And yet it wasn't all fireworks - there was plenty of tenderness and beauty in the slow movement.

He opened his programme with Dvořák's Carnival Overture. While I'm a big fan of Dvořák, this isn't a piece that's ever especially grabbed me before and hence not one I know all that well. From the opening bars I began to wonder why. Bychkov unleashed the LSO in a phenomenal display of energy and precision. It made for a real party piece, full of orchestral fireworks, and an excellent curtain raiser.

After a brief pause while the piano was raised up through the floor (an always fun to watch quirk of the Barbican - much more interesting than just having it pushed on from the back of the stage), Denis Matsuev joined them for Shostakovich's 2nd piano concerto. He proved every bit the match to Bychkov and the LSO. He maintained clarity through some rapid and intricate passages and found all the necessary weight without recourse to thumping the keyboard. Beneath him, Bychkov balanced his forces well, ensuring the pianist wasn't overwhelmed by the comparatively large orchestra. And yet it wasn't all fireworks - there was plenty of tenderness and beauty in the slow movement.

Saturday 27 March 2010

Anyone Can Whistle, or in which it is proved that a Sondheim flop is more interesting than most people's hits

Anyone can Whistle is probably the most rarely performed of all Stephen Sondheim's shows. Even Merrily We Roll Along has enjoyed more rehabilitations. Yet, although on the strength of the new production at the Jermyn Street Theatre it is evidently a show with problems, it is also proof that a Sondheim flop is more interesting, and more worthy of revival, than many hits.

The show takes place in a fictional American town under the tender control of Mayoress Cora Hoover Hooper (Issy van Randwyck) and a nefarious trio of male town council colleagues. In order to save the administration from bankruptcy and ensure her re-election they rig up a fake miracle of water bursting from a rock. Unfortunately the town also houses The Cookie Jar, home to 49 of the socially pressured, or lunatics, who turn up wanting to sample the miracle waters. This of course will disprove the miracle. After that it all gets a bit complicated and zany, somewhat after the manner of the Marx Brothers, with disguises, plots and an increasing confusion between the mad and the sane.

Unquestionably for me, the strongest element in the show is Arthur Laurents' superbly mad book. I don't know what he was smoking when he wrote it, but it is a work of blinding genius ranging from screwball comedy style romance to logical non sequiturs reminiscent of The Goon Show or the Beyond the Fringe crew rambling on about whether or not they have apples in a basket. Given the frequency with which the book element is relegated to second tier status, it is hugely refreshing to be presented with such an intelligent book which demands close listening but equally repays it by being both profoundly touching and uproariously funny.

The show takes place in a fictional American town under the tender control of Mayoress Cora Hoover Hooper (Issy van Randwyck) and a nefarious trio of male town council colleagues. In order to save the administration from bankruptcy and ensure her re-election they rig up a fake miracle of water bursting from a rock. Unfortunately the town also houses The Cookie Jar, home to 49 of the socially pressured, or lunatics, who turn up wanting to sample the miracle waters. This of course will disprove the miracle. After that it all gets a bit complicated and zany, somewhat after the manner of the Marx Brothers, with disguises, plots and an increasing confusion between the mad and the sane.

Unquestionably for me, the strongest element in the show is Arthur Laurents' superbly mad book. I don't know what he was smoking when he wrote it, but it is a work of blinding genius ranging from screwball comedy style romance to logical non sequiturs reminiscent of The Goon Show or the Beyond the Fringe crew rambling on about whether or not they have apples in a basket. Given the frequency with which the book element is relegated to second tier status, it is hugely refreshing to be presented with such an intelligent book which demands close listening but equally repays it by being both profoundly touching and uproariously funny.

Friday 26 March 2010

There's Runnicles, again! The BBCSSO play Webern, Britten and Mahler

It seems like only yesterday when you were lucky to get Donald Runnicles once in a year if you lived in Scotland, so to have him three times in eight days seems oddly surreal. Okay, I'm counting a repeat concert in there, but since I got to go along to the rehearsal and interview the man himself, article and podcast to follow, I think it deserves to be counted as at least one.

In Runnicles' final programme of this year's BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra season we got an interesting mix. First up was Webern's Im Sommerwind. The eagle-eyed will remember this from their concert at the Festival this summer. Again, they made the most of the superbly textured piece, though the reading did seem a little rougher at one or two moments than it had been in Edinburgh.

This was followed by Britten's violin concerto with James Ehnes. It's a fairly early work and as such perhaps not quite so distinctive as some of his later compositions. That said, it had some wonderful touches, such as the recurring timpani motif in the first movement or the piccolo duet. It was helped by some impressively tight ensemble playing, culminating in the astonishing orchestral climax during the third movement which seemed enough to shake the foundations. Ehnes proved a most impressive soloist, technically assured and having a nice tone, especially fine during the long cadenza.

In Runnicles' final programme of this year's BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra season we got an interesting mix. First up was Webern's Im Sommerwind. The eagle-eyed will remember this from their concert at the Festival this summer. Again, they made the most of the superbly textured piece, though the reading did seem a little rougher at one or two moments than it had been in Edinburgh.

This was followed by Britten's violin concerto with James Ehnes. It's a fairly early work and as such perhaps not quite so distinctive as some of his later compositions. That said, it had some wonderful touches, such as the recurring timpani motif in the first movement or the piccolo duet. It was helped by some impressively tight ensemble playing, culminating in the astonishing orchestral climax during the third movement which seemed enough to shake the foundations. Ehnes proved a most impressive soloist, technically assured and having a nice tone, especially fine during the long cadenza.

Saturday 20 March 2010

Promising on paper, but Kamu, Osborne and the SCO leave me cold

In theory, Okko Kamu's programme with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra was perfect: my favourite Prokofiev symphony, a Mozart concerto and a Haydn symphony. Sadly, the evening left me completely cold.

Things got off to a disappointing start with Prokofiev's short but exciting first symphony. Kamu selected volumes that were altogether too great for the small venue. He was also rather clinical at a little too fast. True, the work's excitement does call for a swift tempo, but too swift and you lose something. The central movements lacked any of the wit and charm that make them special and were followed by a breakneck finale. There was some very good playing from the orchestra, but his choices meant it did nothing for me.

If the Prokofiev was disappointing, Mozart's final piano concerto, K595 in B-flat major, was puzzling. Kamu's overly heavy introduction might have been expected, nonetheless it was a shame. Like a sledgehammer to crack a nut, it sapped the beauty from the music. When Stephen Osborne entered, he was good without being great. He was, perhaps, a little heavier than ideal, lacking the poetry of the finest Mozartians, and may be better suited to repertoire such as the Britten and Tippett concerti with which he has recently excelled on disc. That's not to say he was without his moments: there were some nice touches, especially in the cadenzas.

Things got off to a disappointing start with Prokofiev's short but exciting first symphony. Kamu selected volumes that were altogether too great for the small venue. He was also rather clinical at a little too fast. True, the work's excitement does call for a swift tempo, but too swift and you lose something. The central movements lacked any of the wit and charm that make them special and were followed by a breakneck finale. There was some very good playing from the orchestra, but his choices meant it did nothing for me.

If the Prokofiev was disappointing, Mozart's final piano concerto, K595 in B-flat major, was puzzling. Kamu's overly heavy introduction might have been expected, nonetheless it was a shame. Like a sledgehammer to crack a nut, it sapped the beauty from the music. When Stephen Osborne entered, he was good without being great. He was, perhaps, a little heavier than ideal, lacking the poetry of the finest Mozartians, and may be better suited to repertoire such as the Britten and Tippett concerti with which he has recently excelled on disc. That's not to say he was without his moments: there were some nice touches, especially in the cadenzas.

The Scottish CHAMBER Orchestra subscriber concert

I've mentioned before that it's a pity there are only two chamber recitals as part of the official 2009/10 SCO season, which makes the annual subscriber concert all the more a treat. Tickets are free to all subscribers and supporters, and judging by turnout there's a healthy, if somewhat greying, number of both (the demographic seeming significantly more skewed in that direction than the average SCO concert).

It marked the introduction to Edinburgh of the Scottish Chamber Soloists, a wind and piano quartet formed by the orchestra's section principals and pianist Peter Mitchell for some concerts in Nassau. They began, however, with Beethoven's Trio for Flute, Bassoon and Piano, WoO 37. Like many of the 'without opus' works, it is very early Beethoven and it does feel it. It seemed often to be a series of duets, between either piano and bassoon or piano and flute, rather than the genuine conversation that marks out the greatest chamber music. Still, it provided a nice showcase for Alison Mitchell (flute) and Peter Whelan (bassoon) to display some beautiful playing. On the piano, Peter Mitchell (no relation) had a nice delicate touch, though didn't quite bring off the most intricate passages.

This was followed by a new work, written for and commissioned by the ensemble: Rory Boyle's Dance MacAber (a play on macabre). Alison Mitchell explained that they had wanted something with a Scottish feel and that Boyle had mixed Scottish dances with a sense of the macabre and fun. It didn't entirely work. The opening section was a bit too cluttered and the Scottish influences didn't feel very obvious. The slower central section was much more effective, with much clearer melodies and yet still being played with. The final section was again busier, but there was a nice wit to the ending. They played well, having been joined by Maximiliano Martin on clarinet, with Mitchell switching effortlessly between flute and piccolo.

It marked the introduction to Edinburgh of the Scottish Chamber Soloists, a wind and piano quartet formed by the orchestra's section principals and pianist Peter Mitchell for some concerts in Nassau. They began, however, with Beethoven's Trio for Flute, Bassoon and Piano, WoO 37. Like many of the 'without opus' works, it is very early Beethoven and it does feel it. It seemed often to be a series of duets, between either piano and bassoon or piano and flute, rather than the genuine conversation that marks out the greatest chamber music. Still, it provided a nice showcase for Alison Mitchell (flute) and Peter Whelan (bassoon) to display some beautiful playing. On the piano, Peter Mitchell (no relation) had a nice delicate touch, though didn't quite bring off the most intricate passages.

This was followed by a new work, written for and commissioned by the ensemble: Rory Boyle's Dance MacAber (a play on macabre). Alison Mitchell explained that they had wanted something with a Scottish feel and that Boyle had mixed Scottish dances with a sense of the macabre and fun. It didn't entirely work. The opening section was a bit too cluttered and the Scottish influences didn't feel very obvious. The slower central section was much more effective, with much clearer melodies and yet still being played with. The final section was again busier, but there was a nice wit to the ending. They played well, having been joined by Maximiliano Martin on clarinet, with Mitchell switching effortlessly between flute and piccolo.

Friday 19 March 2010

Wagner, Strauss and Beethoven from Brewer and the BBC Scottish (and a new talent from Runnicles)

Why, you might well ask, was I in Glasgow for Thursday's BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra concert? True enough, Donald Runnicles was on the podium, normally sufficient to guarantee my presence, but this was one of two programmes in the current season being repeated in Edinburgh. I bought the ticket in part because my original plan was to be at Jacques Loussier instead of the Edinburgh performance. However, much though I adore what Loussier does with Bach's fifth Brandenburg concerto (it would probably be one of my desert island discs), the chance to interview the man himself necessitated a rethink. But I still had my ticket to Glasgow, and it was worth using for one simple reason: the Glasgow concert had a coda, a brief recital by the evening's soloist, Christine Brewer, accompanied by Runnicles on the piano. You might, perhaps, think it was excessive to have gone all the way to Glasgow just for this. You would, however, be mistaken.

The evening began with Wagner, Runnicles after all being one of the foremost conductors in that repertoire. He had chosen the Prelude and Venusberg Music from Tannhauser, interestingly the same chunk that Mackerras opened a recent concert with. Runnicles took a much slower approach, yet building from the beautifully soft opening of the winds, he whipped the piece into an absolute, and powerfully punctuated, frenzy, so much so that one worried it might overwhelm the Strauss songs that were to follow. But, of course, the piece doesn't work that way, and with a perfect conception of the structure he calmed things back down to the softest of endings. Next month I'm in Berlin to see Runnicles conduct the Ring; if this was anything to go by, we're in for a treat.

Then Brewer took to the stage. I've sung her praises many a time before and there can be little doubt that she ranks amongst the world's foremost sopranos. She has an excellent chemistry with Runnicles and the pair have collaborated to great effect both on disc and in the concert hall. The six Strauss songs they had chosen seemed almost deliberately picked to showcase the range of her voice, which was equally at home above the wonderfully soft, shimmering strings that opened Wiegenlied as it was riding over the powerful climaxes to be found elsewhere. Her exceptional artistry was matched by no less fine playing from the orchestra. It was sufficiently well received that they delivered an encore (Morgen, I think, lieder isn't my speciality so please correct me via the comments).

The evening began with Wagner, Runnicles after all being one of the foremost conductors in that repertoire. He had chosen the Prelude and Venusberg Music from Tannhauser, interestingly the same chunk that Mackerras opened a recent concert with. Runnicles took a much slower approach, yet building from the beautifully soft opening of the winds, he whipped the piece into an absolute, and powerfully punctuated, frenzy, so much so that one worried it might overwhelm the Strauss songs that were to follow. But, of course, the piece doesn't work that way, and with a perfect conception of the structure he calmed things back down to the softest of endings. Next month I'm in Berlin to see Runnicles conduct the Ring; if this was anything to go by, we're in for a treat.

Then Brewer took to the stage. I've sung her praises many a time before and there can be little doubt that she ranks amongst the world's foremost sopranos. She has an excellent chemistry with Runnicles and the pair have collaborated to great effect both on disc and in the concert hall. The six Strauss songs they had chosen seemed almost deliberately picked to showcase the range of her voice, which was equally at home above the wonderfully soft, shimmering strings that opened Wiegenlied as it was riding over the powerful climaxes to be found elsewhere. Her exceptional artistry was matched by no less fine playing from the orchestra. It was sufficiently well received that they delivered an encore (Morgen, I think, lieder isn't my speciality so please correct me via the comments).

Thursday 18 March 2010

Mills unveils his best Edinburgh International Festival to date

Where were you at nine o'clock this morning. Probably you weren't fighting the urge to smash your iPhone to bits as an application froze up, preventing you from downloading the e-mail you'd just received, giving details of the 2010 Edinburgh International Festival. But then you're not me on P-Day, the day the programme is revealed. In the past, such has been my fervour, I've actually taken the day off. This year I had to restrict myself to frantic tweeting in my breaks and picking through the PDF brochure while I wolfed down my sandwiches.

It must be said, we haven't always been totally bowled over by Jonathan Mills' programmes. Indeed, the very title of this website was a dig at his first. It is, therefore, a high compliment when I say I haven't been so excited about a launch since 2006 - a year filled with such legendary performances as the Mackerras Beethoven cycle and Rattle's visit with the Berlin Philharmonic. Last year I didn't go to a huge amount and had substantial other commitments. Even so, I didn't find myself too torn in making choices. This year I have oodles of free time, and yet, already in booking, I'm finding the need to make hard choices, the joy of not being able to go to everything you want to that is so critical to a great festival. So, what lies in wait for us this August?

It must be said, we haven't always been totally bowled over by Jonathan Mills' programmes. Indeed, the very title of this website was a dig at his first. It is, therefore, a high compliment when I say I haven't been so excited about a launch since 2006 - a year filled with such legendary performances as the Mackerras Beethoven cycle and Rattle's visit with the Berlin Philharmonic. Last year I didn't go to a huge amount and had substantial other commitments. Even so, I didn't find myself too torn in making choices. This year I have oodles of free time, and yet, already in booking, I'm finding the need to make hard choices, the joy of not being able to go to everything you want to that is so critical to a great festival. So, what lies in wait for us this August?

Sunday 14 March 2010

Pierrot Lunaire - The Hebrides Ensemble

Given how regularly I bemoan attendance at concerts in Edinburgh which feature contemporary music, it is rather shameful to admit that in five years of living here, I've managed never to hear the Hebrides Ensemble. I'm very glad to have now rectified that.

The programme was presented at the Traverse Theatre, at first glance perhaps not the obvious place for a chamber music recital. And yet, what the Hebrides Ensemble had in mind was to push into the realm theatre in such a way that it suited perfectly where a generally excellent music venue such as the Queen's Hall might not have. It also gave me the opportunity to visit the Traverse (I've never got beyond the bar before, which a friend maintains is the best in Edinburgh - she's wrong, that's the Bow Bar, but I digress). I had been warned about the theatre's extremely steep seating rake, and while I was sufficiently placed in the queue to ensure a fourth row seat, from which both sound and vision were superb, I'm not sure the same would have been true at the very back.

During the Aldeburgh festival last year, I mentioned how much I appreciated Pierre Laurent Aimard's talks, as he explained exactly why the works he'd chosen were paired together. This contrasts with some programmes which seem almost to be selected at random. If anything, last night's theme was clearer still, though artistic director William Conway's brief introduction nicely highlighted the key themes of commedia dell'arte and particularly the figure of Pierrot, and how the works built to evening's culmination in Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire.

The programme was presented at the Traverse Theatre, at first glance perhaps not the obvious place for a chamber music recital. And yet, what the Hebrides Ensemble had in mind was to push into the realm theatre in such a way that it suited perfectly where a generally excellent music venue such as the Queen's Hall might not have. It also gave me the opportunity to visit the Traverse (I've never got beyond the bar before, which a friend maintains is the best in Edinburgh - she's wrong, that's the Bow Bar, but I digress). I had been warned about the theatre's extremely steep seating rake, and while I was sufficiently placed in the queue to ensure a fourth row seat, from which both sound and vision were superb, I'm not sure the same would have been true at the very back.

During the Aldeburgh festival last year, I mentioned how much I appreciated Pierre Laurent Aimard's talks, as he explained exactly why the works he'd chosen were paired together. This contrasts with some programmes which seem almost to be selected at random. If anything, last night's theme was clearer still, though artistic director William Conway's brief introduction nicely highlighted the key themes of commedia dell'arte and particularly the figure of Pierrot, and how the works built to evening's culmination in Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire.

Monday 8 March 2010

John Adams and the LSO batter my heart with the Dr Atomic symphony

I didn't expect Saturday's gloriously played Shostakovich to be topped, but somehow John Adams and the London Symphony Orchestra managed it. After the interval, the composer/conductor took to the stage to introduce his work, talking about how his operas, such as Dr Atomic, Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer, have contemporary themes that resonate heavily and also his attraction to the widely read and cultured character of Oppenheimer. As regular readers will know, I'm not normally a fan of talking to the audience like this, but Adams gave a lesson in how it should be done as he proceeded to comprehensively eclipse the programme note, outlining the work's four sections and the distribution of various vocal parts to members of the brass section.

As someone who's seen Dr Atomic twice, I expected the symphony derived from it to be very familiar. In some ways it was, but more than that it stood by itself. Adams mentioned his desire that it should be more than a simple collection of chunks and he has certain succeeded. Those who heard the much longer first attempt at the 2007 BBC Proms will find a tighter, better focused and, consequently, more powerful work.

Opening explosively with what Adams termed his "Sci-Fi music", it soon became apparent that we were going to be treated to one of the world's finest orchestras on top form. This was underscored in the following "panic" section, fiendishly and thrillingly scored for strings, especially the violins. As the the action moved to the desert and the imminent nuclear test, the opera's arrogant and overweight General Groves was replaced by Katy Jones's superb trombone solo. Many other fine orchestral touches were on show, doubtless present in the opera but which I didn't notice in the theatre, including the atmospheric use bowed symbols and gongs.

As someone who's seen Dr Atomic twice, I expected the symphony derived from it to be very familiar. In some ways it was, but more than that it stood by itself. Adams mentioned his desire that it should be more than a simple collection of chunks and he has certain succeeded. Those who heard the much longer first attempt at the 2007 BBC Proms will find a tighter, better focused and, consequently, more powerful work.

Opening explosively with what Adams termed his "Sci-Fi music", it soon became apparent that we were going to be treated to one of the world's finest orchestras on top form. This was underscored in the following "panic" section, fiendishly and thrillingly scored for strings, especially the violins. As the the action moved to the desert and the imminent nuclear test, the opera's arrogant and overweight General Groves was replaced by Katy Jones's superb trombone solo. Many other fine orchestral touches were on show, doubtless present in the opera but which I didn't notice in the theatre, including the atmospheric use bowed symbols and gongs.

Sunday 7 March 2010

Jansons and the Bavarians PLAY Shostakovich's 10th Symphony

It was a fearsome spectacle. From the outset of Saturday's performance of Shostakovich's 10th symphony, the quality of the sound the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra produced under Mariss Jansons was stunning, wonderfully rich and yet with the kind of unified precision in the strings that one expects from the Cleveland Orchestra. Time and again he whipped them up into furious, frenzied climaxes, the players never missing a beat, and yet so keen was his sense of structure that he was able to transition naturally to the quieter passages and their bleak and depressing landscape without ever losing momentum.

Perhaps most harrowing was the second movement, ostensibly a portrait of Stalin, the militaristic opening powerfully calling to mind his terrors, vast parades of weaponry, and tanks crushing dissent.

Without fail, in solo passages, the members of the orchestra distinguished themselves: violinist Padoslaw Szulc, oboist Stefan Schilli, bassoonist Eberhard Marschall and, especially, clarinetist Stafan Schilling played superbly (I trust those names are correct - the programme lists multiple principals).

Perhaps most harrowing was the second movement, ostensibly a portrait of Stalin, the militaristic opening powerfully calling to mind his terrors, vast parades of weaponry, and tanks crushing dissent.

Without fail, in solo passages, the members of the orchestra distinguished themselves: violinist Padoslaw Szulc, oboist Stefan Schilli, bassoonist Eberhard Marschall and, especially, clarinetist Stafan Schilling played superbly (I trust those names are correct - the programme lists multiple principals).

Saturday 6 March 2010

An extremely self-indulgent blog post about my new Lamy 2000 pens

If you're looking for our normal high brow arts and culture coverage, please avert your eyes, normal service will be resumed shortly. If, on the other hand, you find either fine pens, or finer engineering, of interest, then the following may entertain to you.

I've always had a fascination with fountain pens, I'm sure because of the name. My first encounter, aged something like seven or eight, was for the most part a disappointment: it was with a broken pen which led me to reason that I just could write with fountain pens. Later on, I owned a series of cheap or cheapish Parkers (mainly Vectors and then a thin matt black one, the name of which I cannot recall). My usage ground to a halt for a while after my GCSE maths exam. My pen leaked badly, but I didn't notice until I turned over the page and smoothed it down, leaving a black streak all the way up the column to be used by the examiners only (I still maintain, almost certainly inaccurately, that this is why I have an A as opposed to an A*).

From then until I went to university, I used a series of Pilot V5s, which seemed in many ways to be almost a disposable fountain pen, with the virtue that they didn't leak. However, once at Bristol, I was seized by fountain pen fever once more. It was here, too, that I discovered Lamy. I was in the rather nice stationary shop that used to exist near the top of Blackboy Hill (it may well still do, but I haven't been there for about seven years - it was on the left hand side as the road forked approaching the Downs - and, some Googling later, I find it does indeed and I'm reminded it was called Harold Hockey). Here I saw the Lamy AL-star (pictured above). It is a variant on their basic Safari model with two distinguishing features: first, most of the plastic is replace by aluminium, making for a much nicer build, and, what attracted me to buy it, with transparent sections that allow you to see the workings and how much ink is left. Costing less than £20 then (and not much more now), it's a superb instrument. The feel of the steel nib on paper is actually probably the most comfortable of ANY pen I've used, including my current platinum plated, gold nib. On the downside, though, it isn't the most comfortable to hold and it does leave me with ink on my hands. I still have it, and love it very much (of which more anon). Interestingly, for those who like such things, they now do a pen called the Vista which is totally transparent (which just makes me want it, but I haven't succumbed; yet).

I've always had a fascination with fountain pens, I'm sure because of the name. My first encounter, aged something like seven or eight, was for the most part a disappointment: it was with a broken pen which led me to reason that I just could write with fountain pens. Later on, I owned a series of cheap or cheapish Parkers (mainly Vectors and then a thin matt black one, the name of which I cannot recall). My usage ground to a halt for a while after my GCSE maths exam. My pen leaked badly, but I didn't notice until I turned over the page and smoothed it down, leaving a black streak all the way up the column to be used by the examiners only (I still maintain, almost certainly inaccurately, that this is why I have an A as opposed to an A*).

From then until I went to university, I used a series of Pilot V5s, which seemed in many ways to be almost a disposable fountain pen, with the virtue that they didn't leak. However, once at Bristol, I was seized by fountain pen fever once more. It was here, too, that I discovered Lamy. I was in the rather nice stationary shop that used to exist near the top of Blackboy Hill (it may well still do, but I haven't been there for about seven years - it was on the left hand side as the road forked approaching the Downs - and, some Googling later, I find it does indeed and I'm reminded it was called Harold Hockey). Here I saw the Lamy AL-star (pictured above). It is a variant on their basic Safari model with two distinguishing features: first, most of the plastic is replace by aluminium, making for a much nicer build, and, what attracted me to buy it, with transparent sections that allow you to see the workings and how much ink is left. Costing less than £20 then (and not much more now), it's a superb instrument. The feel of the steel nib on paper is actually probably the most comfortable of ANY pen I've used, including my current platinum plated, gold nib. On the downside, though, it isn't the most comfortable to hold and it does leave me with ink on my hands. I still have it, and love it very much (of which more anon). Interestingly, for those who like such things, they now do a pen called the Vista which is totally transparent (which just makes me want it, but I haven't succumbed; yet).

Tuesday 2 March 2010

Knowledge is the Beginning..... The Rest is Noise

One of the more powerful concert experiences I've had over the years was the visit of Daniel Barenboim and his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra to the Edinburgh festival in 2005. Sadly, back then I didn't review in nearly so much detail as I do now, so my recollections are a pale shadow of the event.

For those who've not come across them, this a project co-founded by Barenboim and his friend, the late Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, to bring together young musicians from across the Middle East to make music together. It's not a completely novel concept, Claudio Abbado's Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester was founded along similar lines, but intractable though the European cold war dividing line was, across which it drew its members, it isn't really comparable. Such an endeavour would be well worth supporting whatever the musical merit. All the better, then, that under Barenboim they rank amongst the finer youth ensembles, having produced concerts and CDs which more than hold their own against professionals.

Paul Smaczyn's film, Knowledge is the Beginning....., charts the orchestra's history, from its inception during Weimar's year as European Capital of Culture in 1999, through to its groundbreaking concert in Ramallah in 2005. There is no narration, save the odd caption. Instead the story is told through the words of the participants, principally Barenboim and, earlier in the film, Said, but with plenty of contributions from the orchestra themselves. It is intercut with scenes of them rehearsing, or playing games in between, some fine concert footage and Barenboim's and the orchestra's travels.

For those who've not come across them, this a project co-founded by Barenboim and his friend, the late Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, to bring together young musicians from across the Middle East to make music together. It's not a completely novel concept, Claudio Abbado's Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester was founded along similar lines, but intractable though the European cold war dividing line was, across which it drew its members, it isn't really comparable. Such an endeavour would be well worth supporting whatever the musical merit. All the better, then, that under Barenboim they rank amongst the finer youth ensembles, having produced concerts and CDs which more than hold their own against professionals.

Paul Smaczyn's film, Knowledge is the Beginning....., charts the orchestra's history, from its inception during Weimar's year as European Capital of Culture in 1999, through to its groundbreaking concert in Ramallah in 2005. There is no narration, save the odd caption. Instead the story is told through the words of the participants, principally Barenboim and, earlier in the film, Said, but with plenty of contributions from the orchestra themselves. It is intercut with scenes of them rehearsing, or playing games in between, some fine concert footage and Barenboim's and the orchestra's travels.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)