The programme was presented at the Traverse Theatre, at first glance perhaps not the obvious place for a chamber music recital. And yet, what the Hebrides Ensemble had in mind was to push into the realm theatre in such a way that it suited perfectly where a generally excellent music venue such as the Queen's Hall might not have. It also gave me the opportunity to visit the Traverse (I've never got beyond the bar before, which a friend maintains is the best in Edinburgh - she's wrong, that's the Bow Bar, but I digress). I had been warned about the theatre's extremely steep seating rake, and while I was sufficiently placed in the queue to ensure a fourth row seat, from which both sound and vision were superb, I'm not sure the same would have been true at the very back.

During the Aldeburgh festival last year, I mentioned how much I appreciated Pierre Laurent Aimard's talks, as he explained exactly why the works he'd chosen were paired together. This contrasts with some programmes which seem almost to be selected at random. If anything, last night's theme was clearer still, though artistic director William Conway's brief introduction nicely highlighted the key themes of commedia dell'arte and particularly the figure of Pierrot, and how the works built to evening's culmination in Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire.

They opened with with Sally Beamish's Commedia, programmed as an Italian Comedy, replete with overture, scenes interspersed with slapstick action, everything, indeed, except actors. Or so the programme suggested, though Sylvie Rohrer, due to play Pierrot in the second half, did move across the stage, in a manner I didn't think entirely worked. As a piece it was a nice enough curtain raiser but didn't sweep me away.

The was followed by Debussy's cello sonata, originally titled Pierrot fache avec la lune (Pierrot angry with the moon), which I last heard from Ades and Isserlis at Aldeburgh. Conway and pianist Philip Moore turned in a sublimely beautiful performance, rich in both colour and texture.

They had, perhaps, saved the highlight of the first half for last, with Helen Grime's Seven Pierrot Miniatures. As student of Britten Pears and Aldeburgh courses, it is perhaps unsurprising that the last time I came across her work was also at Aldeburgh, at the world premiere of her beautiful A Cold Spring. I like a good set of miniatures, finding something immensely satisfying about music that manages to say a lot in a short time and yet to do so without feeling cluttered. Grime had taken seven of the poems from the cycle on which Pierrot Lunaire is based, but which Schoenberg chose not to set. Interestingly, though, these movements are inspired by the poems rather than being settings of them, there is no vocal part and the text was not provided. It didn't matter, so vivid were her compositions. There were some wonderful touches - not least the incredible texture Conway was called upon to produce with his bowing in the early movements or the way, in another movement, the clarinet grew out of nothing, superbly realised by Yann Ghiro. It firmly joins that list of new compositions which one hears and then immediately wishes to hear again. Sadly, I suspect a recording is unlikely.

Even better was yet to come. On paper the choice of Chopin's Valse, op.60 no.2 in C minor, to act as a prelude to the Schoenberg seemed a bit odd. Such doubts were almost immediately erased and it worked a charm as Pierrot waltzed onto the stage. That said, in one or two moments Moore was a little heavy on the keyboard.

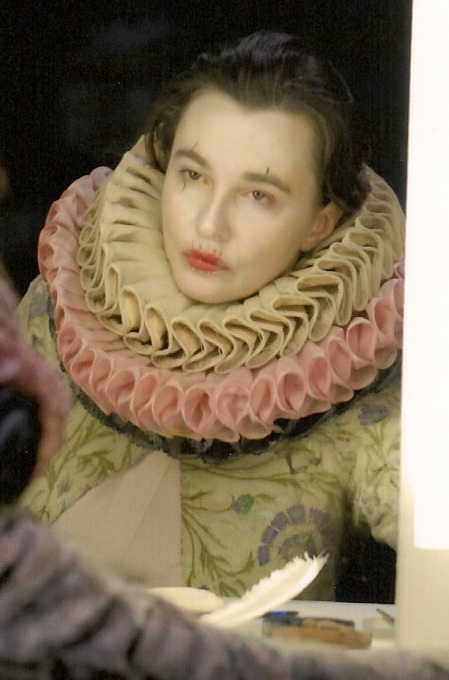

So, then, to the title work. It's difficult to know how to describe Pierrot Lunaire. In many ways it resembles a song cycle: there are, after all, twenty-one poems set to music. And yet, in others it seems clearly intended for the theatre: it seemed entirely fitting that Rohrer was fully made up and in costume and delivered the poems in sprechgesang. In the end, it perhaps isn't overly helpful to get too bogged down in analysing exactly how it might be categorised and rather to sit back and be swept away. The piece is new to me, so I've nothing to compare, but Rohrer completely stole the show for me. Her voice, thin and dreamlike, halfway between speech and song, seemed perfectly etherial. And what acting! I often moan about poor, or overdone, choreography. Not a trace of that, as every twirl, gesture, expression, seemed perfectly natural and utterly captivating. Particularly fine was the way she seemed to move, almost like a marionette. In some ways it was a series of tableaus: now sad, now happy, sometimes funny, now far away.

So captivating, indeed, that she constantly drew one's eyes away from the ensemble who, beneath her, played superbly, realising Schoenberg's wonderfully understated and yet vividly colourful orchestration. True, it might have been nice to have enough light to read the text, or perhaps some form of surtitling (sadly my German tapes in preparation for my April trip to Berlin do not appear to have advanced enough to be any use); yet at the same time it didn't really feel like I was missing out, add to which I'm not sure I'd have wanted the distraction of constantly glancing down at the text. It was, in short, a knockout. I wonder if someone can get them into the recording studio to tape it (Linn - I'm looking at you, or, indeed, you Radio 3).

Throughout, the evening was a lesson in how much can be achieved with modest orchestration, the ensemble comprising only violin, viola, cello, flute/piccolo, clarinet/bass clarinet, and piano. And an impressive calibre of player too: the eagle-eyed (or those glancing through their programme notes) might recognise the SCO's principal flute Alison Mitchell or violinist Alexander Janiczek, who's also ably directed the SCO on several of their discs for Linn, to name but two.

It's worth noting that there did seem to be some amplification going on, as the radio mic snaking back through Rohrer's hair showed (along with the transmitter box visible when she lifted up her coat). But it must have been very subtly done, perhaps for the benefit of those in the upper reaches of the auditorium, because where I was, eyes closed, I'd never have known. Certainly her voice sounded very clearly like it was coming from where she was and not some speakers in the rafters. [Edit - the Hebrides Ensemble inform me that this wasn't for amplification but rather to record the audio for the filming they were doing, which would explain why it didn't sound amplified. I hope we'll get to see the results.]

It was also gratifying to see it sold out - the modern music audience in Edinburgh may not be sufficient to fill the Usher Hall, but it's certainly there. In summary, it may have been my first visit to the Hebrides Ensemble, but I can say with some certainty that it won't be my last.

(P.S. For anyone worried I was sitting there snapping away with my camera, I should assure you that the photos weren't taken by me and should thank the Hebrides Ensemble for providing them.)

No comments:

Post a Comment