“Well, I kinda have two moons in my head, I guess, whereas most people just have one moon. I look at the moon, just like everybody else who’s never been there, and, you know, there it is, and I’ve always thought it was interesting, whether it was full or just a sliver, or what have you. But every once in a while I do think of the second moon, you know, the one I that I recall from up close, and it is kinda hard to believe that I was actually up there.”

Michael Collins speaking in the 2007 documentary In the Shadow of the Moon. It remains one of the greatest records of the Apollo programme, not least due to the wit, the poetry, and the sparkle of Collins’ interviews. It is also one of my favourite films, and Collins my favourite Apollo astronaut and a real inspiration, so the news of his death last week from cancer at the age of 90 was particularly sad.

Collins has an interesting place in history: the closest person to the historic landing of Apollo 11 who isn’t a household name. Everyone knowns who Neil Armstrong was and can quote his famous words. Most people know or recognise Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin’s name. Not so Collins. Many of the pieces written in wake of Collins’ death have focussed either on this status as a forgotten person of history, or of his supposed extraordinary loneliness on the dark side of the moon, but that wasn’t how he saw himself. As he wrote in the preface to 2009 edition of his autobiography Carrying the Fire:

“On my tombstone should be inscribed LUCKY because that is the overriding feeling I have today. Neil Armstrong was born in 1930, Buzz Aldrin in 1930, Mike Collins in 1930. We came along at exactly the right time.”

Luck was there throughout his life. For example, there was the decision to go into the Air Force, which would eventually lead to flight test at Edwards, breeding ground for many an astronaut. He did this in part because his father and other relatives were Army royalty and he wanted to avoid any change of favouritism. Had he not had this humility, he might not have gone to the moon.

Luck struck later when he suffered back problems and was pulled from the crew of Apollo 8, the mission that would go on to make the first trip to orbit the moon, the first flight to escape earth, and the flight that captured the iconic earthrise photograph. Of course, had he flown on 8, he would have been out of the roster for 11, and possibly even ended up on in the ill-fated 13.

Collins didn’t always have the best luck with photography either. On Gemini 10 he was one of NASA’s early spacewalkers and trying out a new compressed air gun for manoeuvring. Results were… mixed… and are vividly recounted in Carrying the Fire. These forty, somewhat tense, minutes included struggling with the realisation that the Agena module had been designed with “no ready handholds”, and literally reaching the end of his tether. At one point he worried that his motion would cause him to speed up as the tether shortened and wrapped round the Gemini spacecraft (exactly as happens when spinning ice skaters draw in their limbs, and as doesn’t happen for some reason during the final implausible rescue in The Martian). Fortunately, he was able to escape this fate, but alas his camera didn’t:

"In addition, I have taken quite a few other exposures along the way, so that this roll of film must have at least a dozen of the most spectacular pictures ever taken in the space program—wide-angle pictures of Gemini, earth, and Agena—and now it is gone! I can’t see the camera anywhere, but the lanyard dangles forlornly from my chest pack, making aimless little pirouettes to draw my attention to it. Each time the camera came loose and banged around, the screw must have backed off a little bit, until finally—pfft! Adios, beautiful pictures."

Yet Collins had his lucky photography moment in the end, with his own version of the earthrise. And, in true Collins style, he added an epitaph that elevated it. It was caught as the ungainly Eagle, the lunar module, returned to the Columbia command module for the return trip to earth.

Everyone who's ever lived is in this photo... except Michael Collins.

He had a way with words, and one of the regrets that he did have was a missed opportunity in this area. Serving as Capcom (capsule communicator, always an astronaut, and the member of mission control whose job it was to relay instructions between the ground crew and spacecraft) for Apollo 8, he was on duty when the mission left earth’s influence for the first time. But he regretted not having done the moment justice within something more than “You are go for TLI”, having thought that someone else would be marking the occasion.

Indeed, in his book, Collins argued for STEEM over and above STEM. I.e. that science and engineering weren’t enough without a strong grasp of English to make your case. Many, myself included, would go further: one often sees A added for Arts. And, indeed, the creativity of many of the solutions to the problems that arose during the programme is an excellent argument for that. Collins himself was not without artistic skill, playing a role in designing the famous mission patch:

He was unusual in his eloquence: he could really write. Not for nothing is Carrying the Fire routinely cited as the best astronaut autobiography. He wrote it himself – no ghost writing here. Compare, say, with John Young’s book. Young had a fascinating life and career, including not one, but two trips to the moon, the first flight on the space shuttle, and sharing the Gemini 10 mission with Collins, yet his book often feels flat, or like a dump out of his flying log. Presumably because that’s exactly what the ghost writer is drawing on at that moment.

Collins' eloquence shines, time and again through his descriptions of that historic mission to the moon, whether in Carrying the Fire, or his interview, such as for In the Shadow of the Moon. It applies in small moments, such as settling a debate between Apollos 8 and 10 as to whether the moon is more grey or slightly brownish, or on more profound questions such as whether he was really the loneliest man in history, since Adam, as one commentator had it.

“I discovered later that I was described as the loneliest man ever in the universe, or something, which really is a lot of baloney. I mean, I had mission control yacking in my ear half the time… I rather enjoyed it. I certainly was aware of the fact that I was by myself, particularly when I was on the back side of the moon. You know, I can remember thinking, God, you look over there and there’s 3 million people, plus 2, somewhere down there. And then over here there’s one God only knows what. So, you know, I felt that strongly, but I didn’t feel it as loneliness, I certainly didn’t feel it as fear, I felt it as awareness, almost a feeling of exhalation. I liked it, it was a good feeling.”

Michael Collins - In the Shadow of the Moon

He captured too the sense of worry around the fragility of the endeavour and the weight of the mission and the expectations they carried. But always with a lightness and humility:

“I had the feeling the whole world was watching us. So, not only do I have a lot of things I can do wrong, but the consequences should I do them wrong are going to be immediately obvious to 3 million people, and that’s a worrisome thought… It’s not fear, it’s worry; and I think there’s a legitimate distinction between the two. So it’s not a question of you’re scared all the time, but it is you’re mildly worried all the time, or at least I was. You know, you’re not sure all these things are going to work properly, and there’s a hell of a lot of them coming in a very fragile daisy chain, and you don’t want any of those links in the chain to break because downstream from that broken link they’re all useless.”

Michael Collins - In the Shadow of the Moon

Of course, ultimately, he needn’t have worried, “because everything worked as it was supposed to. Nobody messed up. Even I didn’t make mistakes!” Luck, perhaps, was on his side.

From left to right: Armstrong, Collins, Aldrin in quarantine following their return from the moon.

This of course, is primarily an arts and culture blog. I’ve noted the brilliance of Collins' autobiography, which everyone should read. So too In the Shadow of the Moon, which everyone should watch. A film largely without narration which tells the story of the Apollo programme in the words of the astronauts. I reviewed it here at the time of the release.

Alas, Collins didn’t always fare so well on film. Sometimes this was down to neglect. Among the long litany of things that were wrong with First Man, of which there are far too many to go into here without wandering a long way from the point, is the treatment of Collins. Lukas Haas’s portrayal is so one dimensional and devoid of charm you wouldn’t know he was playing Collins if you saw any of the clips out of context. In fairness to Haas, director Damien Chazelle and writers Josh Singer and James Hansen probably deserve more blame: I genuinely thought we might get to the moon and back without him having a single line of dialogue.

Of course, the film is primarily about Armstrong, but he’s such a blank slate in so many ways that it’s an odd choice not to show some of the colour around him, even just to provide contrast or relief. Why wouldn’t you put in this exchange, as Armstrong and Aldrin depart for the moon:

Columbia (Collins): I think you've got a fine looking flying machine there, Eagle, despite the fact you're upside down.

Eagle (Armstrong): Somebody's upside down.

You might image that Collins would fare better in 2019’s Apollo 11, made for the 50th anniversary of the flight. The documentary is not without its moments. Buckets of astonishing 70mm film were rediscovered, and the result is some scenes presented more cleanly and dramatically than I have ever seen them. When viewed on IMAX, the impact of sequences such as the rollout of the mighty Saturn V on it’s gigantic tractor, crawling towards the launchpad, humans scurrying around beneath like ants, is jaw-dropping. The launch sequence too is the cleanest I have ever seen it, and the detailing on moments like the staging is remarkable.

Yet despite this, it represents a missed opportunity and seems fundamentally lazy and pedestrian. Sure, there is good archive footage, but that’s it, and good archive footage does not a documentary make. I suppose it gives you some sense of the moment, but I can’t help feeling that ninety minutes of archive footage, almost entirely from the mission itself, in order, is a little, well, dull, and one for real space geeks only.

There is no narration, no interviews. This means that if you don’t know the story behind the 1202 programme alarm, well, you’re on your own. True, it has fractionally more of the Collins charm: you do get the upside down exchange, but that’s about it. You don’t really get any of the sense of the rivalry between Armstrong and Aldrin or who any of these people were.

Worse, while there’s some great footage, it is patchy. There are big chunks of the mission where it’s poor to non existent. And while at times you can justify this - you have to make do with the one small step shots as they are - other less historic segments segments have to be put together with photographs. David Sington makes a much better decision with In the Shadow of the Moon to sometimes illustrate one mission with footage from another, thus enabling him to actually tell the story. He also knows the value of an interview.

Apollo 11's heavy handed score doesn’t help either. Driving, wannabe Hans Zimmer, in the way that seems to be obligatory for anything connected to space these days, it, like that for First Man, which renders key dialogue almost in audible during the descent, almost gets in the way. Contrast with Philip Sheppard’s magnificent score for In the Shadow of the Moon (notable also for the contributions of a young Peter Gregson), which knows how to be light, how to soar with the X-15 flights or the Saturn launch. He knows the images are pounding, that you need the score to do something else. In fairness, Hans Zimmer knows this too, and his score for Interstellar is a masterpiece, but that’s for another time.

If First Man and Apollo 11 represent an odd omissions, For All Man Kind embellishes in a way that misses the point very differently. Of course, this is intended as a science fiction alternative future rather than a biopic or historical dramatisation, and yet I think that when you’re portraying real people, who have put on record what they would have done in certain situations, you need a pretty good reason to turn that on its head. Or you just need to be lazy and not check, which seems more likely. It’s part of what makes the show a little disappointing and somehow slightly less than one might expect from Ronald D Moore, who cut his teeth on the best Star Trek – Deep Space Nine (that’s a hill I’ll die on!) – and gave us the great version of Battlestar Galactica.

Yet in For All Man Kind two odd things happen. First of all, Apollo 11 goes awry and Collins, when ordered to come back says he’s discussed this with the others and intends to stay and die in orbit of the moon. Perhaps this Collins isn’t intended to have a family, but it makes no sense, and is totally at odds with his own words. As he wrote in Carrying the Fire:

"My secret terror for the last six months has been leaving them on the moon and returning to earth alone; now I am within minutes of finding out the truth of the matter. If they fail to rise from the surface, or crash back into it, I am not going to commit suicide; I am coming home, forthwith, but I will be a marked man for life and I know it. Almost better not to have the option I enjoy."

It doesn’t make sense dramatically either. But then fictional portrayals of astronauts rarely do. Too often they are shown as lunatics with no regard for procedures who inexplicably haven't been grounded. Perhaps the belief is that doing things in a more realistic manner wouldn’t be dramatic. This totally ignores all the tension and drama that very often was present, such as that famous 1202 programme alarm. (This was the result of Dr Rendezvous, Buzz Aldrin, leaving the rendezvous radar on at the same time as the landing radar. Fortunately Margaret Hamilton and her team at MIT had built the software in such a way that this didn’t cause everything to grind to a deadly halt.) Then there’s the loose bit of solder on Apollo 14 that nearly scrapped that landing. And, of course, Apollo 13.

Perhaps some people making space films have never seen Apollo 13. It has all the tension you could possible want, despite you knowing what happens, but, alas, does not feature Collins, for he had, by this point, left NASA.

Later, in For All Mankind, Collins who for reasons never explained hasn't left NASA, does, almost, get another flight on Apollo 23. On the one hand, it is nice to see him finally getting the opportunity of the commander’s seat, and yet again we get a portrayal which misses the option to showcase someone much more interesting. Collins knew he probably could have had another, better seat, but he just didn’t want it:

It would have taken another two years, I thought (actually, as it turned out, if I had been assigned to Apollo 17, it would have taken well over three years), and I was simply not willing to spend that many days in simulators and nights in motel rooms instead of with my family.

Michael Collins – Carrying the Fire

The story of the early astronauts is often one of men, no women allowed (one thing For All Mankind does seek to address well), single-minded in their desire be the best, to go “higher, further, faster”, or as Tom Wolfe memorably put it in The Right Stuff, it was:

“like climbing one of those ancient Babylonian pyramids made up of a dizzy progression of steps and ledges, a ziggurat… and the idea was to prove at every foot of the way up that pyramid that you were one of the elected and anointed ones who had the right stuff and could move higher and higher and even—ultimately, God willing, one day—that you might be able to join that special few at the very top, that elite who had the capacity to bring tears to men’s eyes, the very Brotherhood of the Right Stuff itself.”

Tom Wolfe – The Right Stuff

And everything else fell to the wayside, which generally meant their marriages and families. Yet Collins was one of the very few astronauts of the era, and the only one of the Apollo 11 crew, who remained married to the same woman, Patricia, until her death a few years ago.

Fortunately, there is one portrayal that got Collins, and so much else, right: HBO’s landmark From the Earth to the Moon. Based on Andrew Chaikin’s book A Man on the Moon, and produced by Tom Hanks and Ron Howard a few years after Apollo 13, it aims to tell the story of the entire Apollo programme. At the time it was HBO’s most expensive miniseries with a budget of nearly $70m for the twelve episodes. It’s uneven, but the highlights magnificent. These include the tumult of 1968 capped by the triumph of Apollo 8, the tragedy of Apollo 1, the ingenious story of the design of the lunar module in Spider, the role of science and Apollo 15 in Galileo was Right, and impact on their families in The Original Wives Club.

Collins features most prominently Mare Tranquilitatis which focuses on the first landing. Here we have Tony Goldwyn as the introspective Armstrong. Opposite him we get Bryan Cranston in a wonderfully rounded portrayal of a man on whom, to quote Collins’ potted biography from Carrying the Fire: “Fame has not worn well… I think he resents not being first on the moon more than he appreciates being second.” Cranston shows First Man's Corey Stoll how it's done, though again, Stoll had a script devoid of any nuance to work with so we shouldn't be too harsh.

Between them we are treated to Cary Elwes who nails the easy charm and light wit that one sees in interviews or enjoys from his writing. The appreciation at simply being there. To quote again from In the Shadow of the Moon:

“I was pigeon-holed, if that’s the right word, as a Command Module Pilot, so I lost my chance of walking on the moon, but in return for that, I gained a chance of a fly to the moon and perhaps be a member of the first crew to land on the moon.”

Michael Collins – In the Shadow of the Moon

Time and again, this sense of joy and humility is what makes Collins so endearing. After returning to earth, the crew were showered with accolades, addressed congress, and travelled the world. Collins was struck by the reaction of people, the appreciation of a feat of human ingenuity rather than viewed simply through a prism of nationalism.

“After the flight of Apollo 11, the three of us went on a round the world trip. Wherever we went, people instead of saying, well, you Americans did it, everywhere they said we did it, we humankind, we the human race, we people did it. And I’d never heard of people in different countries use this word we, we, we, as emphatically as we were hearing from Europeans, Asians, Africans; wherever we went it was ‘we finally did it’. And I thought that was a wonderful thing; ephemeral, but wonderful.”

Michael Collins - In the Shadow of the Moon

After walking away from NASA, he served briefly in in the state department for the Nixon administration, but this doesn’t seem to have suited him:

“My only regret is that I left State before I had an opportunity to attend a really high-level diplomatic confrontation and write the press communiqué describing it. Instead of the canned description, “a frank and productive interchange, in a cordial atmosphere,” which covered all meetings of all types, I wanted—just once—to tell it like it was. “It was a useless and futile session. His Excellency was as stubborn, pigheaded, and recalcitrant as usual, and in fact I think the surly bastard was drunk.”

Michael Collins - Carrying the Fire

Luckily he found a more suitable role at the Smithsonian where he founded the National Air and Space Museum on the Mall, whose exhibits included the command module from Apollo 11. In contrast to the reclusive Armstrong, he always seemed ready to talk about his experiences, for example in the recent BBC podcast 13 Minutes to the Moon or on the 50th anniversary of the flight. And, of course, In the Shadow of the Moon.

I watched the film again this week. At a couple of pounds on Amazon Prime I've more than had my money from it over the years, even if it does continue to grate that some moron has ensured the icon is a photo from a much later space shuttle mission. Maybe this is because in the UK it's the Channel 4 edit and perhaps they don't have the rights to the poster or something crazy like that.

I watch it often in my role as an uncle: it's important to instil a love of space at an early age. When I first started, at somewhere between two and three, we just focussed on the money shots such as the Saturn V launch and the lunar rover (or moon car), skipping over the interviews. But within a year or two, my niece was asking me to let the interviews play which, with the exception of the scarier parts, I generally did. We listen and discuss over coffee (or frothed milk) and I'm especially proud she's learnt to recognise Michael Collins. Often, as we go through, the one question she'll ask me of the interviewees is "is he dead?"

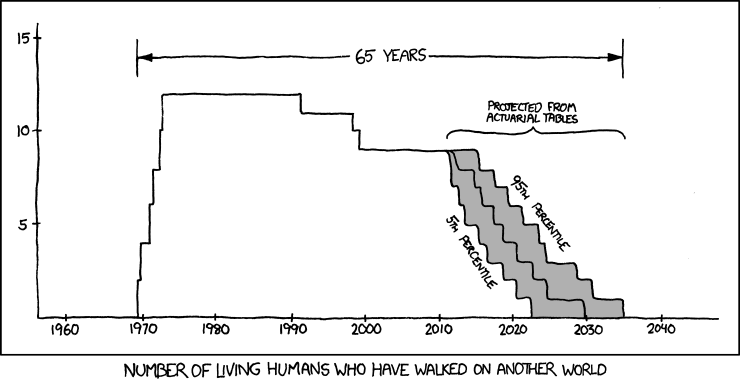

John Young, yes. Charlie Duke, no. Gene Cernan, yes, Dave Scott, no. I think of the poignant xkcd cartoon. And, even though, Michael Collins isn't included on the graph, there'll still be a lump in my throat the next time she asks me.

I opened this piece with a quote from that In the Shadow of the Moon, and it seems a fitting place to end it.

“I think, if you do something as drastically different like flying to the moon and coming back again, everyone tells you how important it is, how wonderful it is, and how important, important, important, then by comparison a lot of other things that used to seem important don’t seem quite as much so. And I’m not saying that I’m able to I face life with greater equanimity because I’ve flown to the moon, but I try to.”

No comments:

Post a Comment